By Anirban Mukherjee

The battle of fish market

Abishek, an upper caste Bengali I.T. professional in his mid-thirties, is not a Modi–bhakt who fails to see anything wrong with any of the decisions taken by the present government. Being a private sector employee, he is not delusional about acche din (days of prosperity) and, in fact, he is apprehensive about of Indian economy’s impending doom. Therefore, when he tells me that National Registry of Citizens (NRC) is a necessity to keep the illegal immigrants at bay, he forces me to rethink my anti-NRC. position. Hailing from a North-Eastern suburb of Kolkata which lies around 60 km from the India-Bangladesh border at Petrapole, Abhishek is no stranger to interacting with immigrants from Bangladesh. He observed that his neighborhood was being flooded by Bangladeshi immigrants, who, according to Abhishek, are goingto the local markets with pocket full of cash and driving the fish prices beyond the reach of the common people (I, however, find this ironical as the best Hilsa, the fish coveted most by the Bengalis, also comes from Bangladesh and can also be called an immigrant fish!). Like most other Bengalis, Abhishek can probably identify Bangladeshis, from their accent which is very distinct from the accent in which Bengalis speak in and around Kolkata but there is no way for Bengalis on this side of the border to identify if a Bangladeshi has entered India by legal means. This is where I begin my enquiry, by putting on Abhishek’s hat. Let us assume that Abhishek is right, his neighborhood is indeed being flooded by illegal Bangladeshi immigrants. But is Abhishek’s experience in his neighborhood near the India-Bangladesh border an actual representation of the entire state of West Bengal?

Let me illustrate this with an analogous example. We often see many Africans come to Kolkata to play in various football clubs here in the city. Suppose that 20 African immigrants live in an apartment with 80 Indian residents, making the total number of residents 100. Now if an Indian resident of the apartment, say Mr. Chatterjee, solely relies on his own experience to form perception about the social reality, he would believe that 20% of Indian population consists of immigrants from Africa! Needless to say, such perception does not truly reflect the reality. Formation of such erroneous belief comes from the practice of treating one’s own experience as the general truth.

We therefore have to treat Abhishek’s experience with caution and ask the following question: does Abhishek’s reality represent the general reality of West Bengal? Or is it the case that Abhishek’s opinion stems from his individual experience which is a special case and does not call for a more general policy response?

Illegal immigrants: where is the evidence?

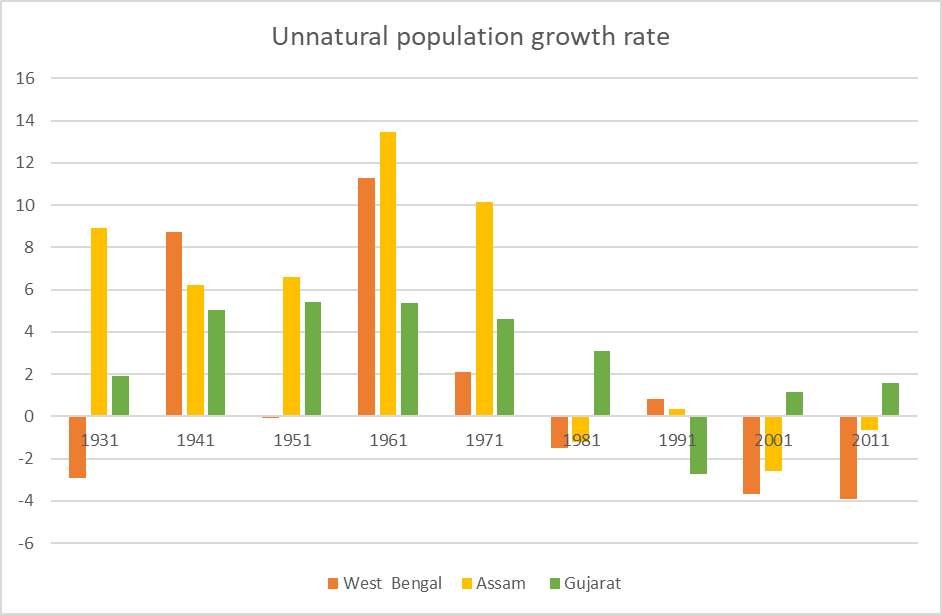

Is there any way to check whether West Bengal is in fact experiencing a very high influx of illegal immigrants from Bangladesh? After all, an illegal immigrant will not declare his/her true status. The only, albeit imperfect, way to capture any surge in illegal immigration is to look at publicly available data; in this case, I analyse the census data to find out the population growth in West Bengal. But population rises naturally whenever birth rate exceeds death rate. It can also rise if people from other states come to West Bengal in search of jobs. How do we know whether population is rising because of illegal immigration from Bangladesh or because of natural reasons? We unfortunately cannot differentiate between these two mechanisms. Nevertheless, we argue that if a state’s population is rising at an unusually high rate, it is very likely that the state is experiencing immigration. This leads to another critical question: what is an unusually high number for population growth rate? This leads to another critical question: what is an unusually high number for population growth rate? In answering this we take a simple approach. We argue that the population growth rate for the entire country is the natural rate of population growth. A state is experiencing an unusually high rate of population growth if its rate of population growth exceeds that of the country. Based on this approach we propose a simple measure – we calculate the difference between state’s population growth rate and India’s population growth rate. If its value is positive for a state, the state is experiencing unusually high population growth (hence a possibility of immigration), and if it is negative, it is unusually low. It is not difficult to come up with a criticism of this measure, but this is the only measure we can construct using publicly available data that can capture unusual level of migration. I call the variable created by deducting India’s population growth rate from state’s population growth rate unnatural population growth rate. The nomenclature – unnatural population growth rate – is based on the premise that the national population growth is the average, and therefore the natural one. I calculate the value of the variable for West Bengal, Assam, and Gujarat – West Bengal and Assam are the obvious choices being the two major neighboring states of Bangladesh; Gujarat is kept as a comparison state.

Before proceeding any further, we need to check the suitability of our measure in capturing phases of high migration from Bangladesh. After all, population can increase due to natural reasons as well. One way of checking the fitness of our measure is to look for its values in episodes of history known for high level immigration into our country from our neighboring Bangladesh – India’s independence (1947) and Bangladesh’s war of liberation (1971).

If we look at the population growth rate comparison, as shown in Figure 1, in 1951 (census) right after our independence, we find that West Bengal’s population growth rate (13.1%) was almost equal to the national population growth rate and as a result the variable unnatural population growth rate takes a value close to 1 for the period 1941-1951. In this year Assam’s population growth rate showed a significant rise above the national level and so did Gujarat’s. Assam’s rise is consistent with post-independence refugee crisis, but West Bengal’s value is puzzling. One possibility can be that the government machinery of West Bengal at the time was so busy managing the refugee crisis that the census was not properly done. There is an indirect support for this hypothesis from 1961 census figures which show a big rise in the population growth rate for West Bengal. The next known episode of high-level immigration was during the liberation war of Bangladesh in 1971. It created a high spike in Assam’s population growth rate (34.95%) which was higher than the national rate (24.8). The population growth rates of West Bengal (26.86) and Gujarat (29.39%) were also high but not as high as that of Assam.

However, the situation started to change from 1981 census, almost coinciding with the time liberalization of Indian economy started in mid-eighties and Bangladesh started becoming a major player in garments export. I will explain later that this was not a coincidence. But for now, let us have a quick look at the census figures spanning two decades from 1991 to 2011. For most of the census reports, Assam and West Bengal’s population growth rate was lower than that of India, only exception being 1991, when the population growth rates of Assam (24.24%) and West Bengal (24.7%) was higher than that of India (23.9%). In this year, Gujarat’s population growth rate (21.19%) was lower than that of India. For the next two census rounds the pattern was just the opposite: Assam and West Bengal’s population growth rates were lower than that of India, while Gujarat’s population growth rate was higher.

In this essay, my argument is based on the premise that a high volume of illegal immigration would reveal itself through an abnormal rise in population figures. From the discussion made above, we do not see any such rise in population growth rates for West Bengal and Assam in the most recent rounds of census, which means that in reality there is no systematic evidence in favor of Bangladeshi immigration hypothesis that has continued to capture the imagination of many Indians. That does not mean Abhishek was wrong – he may indeed be losing the battle of fish market to illegal immigrants from Bangladesh. But the numbers, in the macro perspective, are not big enough to justify the costs brought in by laws such as NRC.

Where have all the immigrants gone?

However, there is one caveat. When I started showing this data around, people raised objection against my hypothesis saying that immigrants from Bangladesh are indeed entering West Bengal, but they are moving to other states making the population figure for West Bengal low. Can they be right? Is West Bengal’s population growth rate lower than Gujarat because illegal immigrants are using West Bengal as corridor and upon entering India, moving to some other states? I start by looking migration data for Gujarat for the year 2011. Between 2001-2011, the number of people who moved to Gujarat from outside for work is around 6,50,000 (5,34,545 from rural area and 1,22,241 from urban areas outside the state). Between 2001 and 2011, the absolute increase in Gujarat’s population was 98,67,675. Without the migrated population, Gujarat’s population growth rate between these two time periods would have been 18.19% which is lower than the actual population growth rate recorded in Gujarat (19.28%) but still higher than the population growth for entire India (17.7%), West Bengal (13.8%), and Assam (17.07%) for that period. However, there is more to it. Gujarat, a state characterized by high economic growth, is attracting migrants from all over India. Hence, only a fraction of these migrants is Bengali. We cannot possibly know if a Bengali migrant is an illegal immigrant from Bangladesh. But if we can calculate the number of Bengali migrants to Gujarat, we can calculate an upper bound of Bangladeshi immigrants entering Gujarat – in the worst case scenario, all Bengali migrants can be Bangladeshis. But how many migrants are coming from West Bengal? Is it possible to have an estimate of the Bengali migrants coming to Gujarat during this period? I adopt an indirect approach.

Indian Census publishes mother-tongue wise distribution of population across states. By using these figures, I try to indirectly arrive at an estimate of Bengali speaking migrants to Gujarat. In 2011, there were 79,648 people living in Gujarat who reported Bengali as their mother tongue. In 2001, this number was 40,780. Hence, in Gujarat, the number of Bengali speaking increased by around 40,000 between 2001 and 2011. But this number 40,000 constitutes the upper bound of Bengali migrants entering Gujarat, which is .06% of Gujarat’s population. If we leave these people out and calculate Gujarat’s population growth again, it will not make much difference to the actual population growth rate of the country. This shows that the high population growth rate experienced by Gujarat after 2000 cannot be explained fully by migration from West Bengal.

One may argue that Gujarat is not the right destination state and we should be looking for illegal immigrants from Bangladesh that are moving to some other state. Anecdotal evidence suggests that one such possible state can be Karnataka which came to news headline recently when a slum of Bengali migrant workers in Bengaluru was demolished with allegations that they are illegal immigrants. Karnataka is also important because Bengaluru, its capital, is the destination of many high educated, software engineers from West Bengal. The total number of Bengali speaking population living in Karnataka in 2001 was 41,256; it rose to 87,963 in 2011. Hence, the difference – 46707 – can be the maximum number of Bengali (or Bangladeshi) migrants that have entered Karnataka between 2001 and 2011. One does not need to be a mathematical genius to figure out that for Karnataka, a state with a population of 6 Crore (60 million), this is not a significant number. In order to illustrate my point in a systematic manner, I create another variable – the increase in Bengali population in a state as a proportion of the general increase in that state’s population – to check whether different states’ population growth rates are indeed being driven by growth in the Bengali migrants to these states. Rather than doing it for all the states, I take the ones for which anecdotes of Bangladeshi immigrants float around in common parlance – namely Karnataka, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, and Delhi NCR, along with Gujarat. I find that not even 1% of the population growth in these states can be explained by influx of Bengali migrants to these states. The highest is Maharashtra, where Bengali population growth is .85% of total population growth. See figure 2.

To drive my point further, I do a macro exercise. The diagram shown below (Figure 3) plots three data points from 2011 census – West Bengal’s population, people living in West Bengal who report Bengali as their mother-tongue (loosely referred to as Bengalis in West Bengal) and people in India who report Bengali as their mother tongue (again, loosely termed as Bengali in India). (Note that these are accumulated total – so they include Bengalis living in other states and non-Bengali speaking people living in West Bengal (Marwaris for example) for generations.). If the corridor theory of illegal immigrants – that postulates that Bangladeshi immigrants are using Bengal as a corridor and upon entering India they spread to different states – is correct then the Bengalis living in India would have outnumbered Bengalis living in West Bengal and surpassed the population of West Bengal by a big margin. But that is not the case. There are around 97 million (8% of India’s population) Bengali speaking people in India of which 78 (6% of India’s population) million live in West Bengal. So, there are 20 million Bengalis living outside Bengal.

Is this a high number? We use non-Bengali speaking people living in West Bengal as a reference point. After all, they live in a state where majority people do not speak their mother-tongues. West Bengal’s population is around 91 million (7% of India’s population) of which 78 million speak Bengali. Hence, the number of people living in West Bengal who do not speak Bengali is 13 million. To sum up, there are 20 million Bengalis living outside West Bengal and 13 million non-Bengalis live in West Bengal. These 13 million people are the result of legal, inter-state migration happening for centuries – Marwaris migrating to West Bengal can probably be traced back to 300 years, if not more. Given that inter-state migration usually happens in search of economic opportunities which are rather limited in West Bengal, this 13 million can be seen as a lower bound of inter-state migration. We may reasonably expect that states like Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Karnataka will attract many more migrants from other states. In this perspective, 20 million Bengalis (1.6% of India’s population) living outside West Bengal does not seem unnatural at all and, therefore, does not provide any evidence in favor of the corridor theory of illegal immigrants.

“The answer my friend is blowing in the wind”

The question that remains to be answered is how to reconcile Abhishek’s micro-level observation with this macro data. I have already hinted at the answer in the beginning – Abhishek is probably not wrong. He indeed is meeting people speaking Bengali differently who, with a high probability crossed the border illegally. It is just that the number of such people, which seems quite significant if compared to total number of people Abhishek meets every day, is insignificant when compared to the national population. From the graph of unnatural population growth (Figure 1), it is quite evident that the turn-around of population growth rate for West Bengal started in 1981and got strengthened from 2001. This cannot be just coincidence. People migrate to places which provide better economic opportunity than their place of origin. The economic position of West Bengal started to decline from the early 1980s while Bangladesh’s garments revolution started in mid 1980s. These two things together reduced the net gain from immigrating to India. This can be one possible explanation of the population growth rate turn-around for West Bengal. In this article I tried to show that there is no evidence of large-scale immigration from Bangladesh in the recent past even though this has been used as a polemical argument in favor of NRC. An act such as NRC is costly for the economy and the social fabric of India. If there is nothing in the data that justifies such costs, the government should rethink its position and divert its resources to more productive purposes.

Bio:

Anirban Mukherjee is an assistant professor at the Department of Economics, University of Calcutta. Before joining University of Calcutta, he taught at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur. His interest areas for research are institutional economics, political economics, development economics and economic history. His current research projects involve issues related to identity politics, gender disparity in workplace and effect of court quality on entrepreneurship.

***

Like Cafe Dissensus on Facebook. Follow Cafe Dissensus on Twitter.

Cafe Dissensus Everyday is the blog of Cafe Dissensus magazine, born in New York City and currently based in India. All materials on the site are protected under Creative Commons License.

***

Read the latest issue of Cafe Dissensus Magazine, “Pandemics/Epidemics and Literature”, edited by Nishi Pulugurtha, Kolkata, India.