By Neera Kashyap

Anju Makhija wears many hats. She is a poet, playwright, anthologist, translator and columnist. She has written/co-edited 14 volumes which include poetry, anthologies, translations, plays and children’s books. Her poems from two earlier poetry collections, Pickling Season and View from the Web have won several awards. A Sahitya Akademi awardee for translation, her translation with Hari Dilgir from Sindhi of Shah Abdul Latif, the 16th century Sufi poet, Seeking the Beloved is regarded as an authoritative work on the mystic. She is also translating the 17th century Sufi poet, Sachal Sarmast. Her myriad plays include: The Last Train, a political satire (shortlisted for the BBC World Playwrighting Award, 2009), the popular, Meeting with Lord Yama and a musical with original songs, Off the hook.

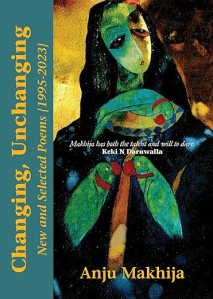

Besides being a biographical journey, it is this diversity of talent in multiple genres that is reflected in Makhija’s new collection of poems, Changing, Unchanging: New and selected poems (1995-2023), published by Red River. In her Preface to Mumbai Traps, 2022 (Makhija’s collection of six plays), Uma Narain, Founder, School of Liberal Arts, Mumbai writes: “The characters in the plays are chroniclers of the follies and foibles of Mumbai life and the playwright neither evaluates nor judges from a moral high ground….The magic is created by familiarity with theatre arts, the poetic sensibility, a translator’s transformative power and a knack for finding the funny bone.”

In her preface, Editor of Samyukta Poetry, Sonya J. Nair sees Makhija essentially as a seeker: “We need more intrepid explorers like her – those who go deep into the mind, the core of the earth and return with the very Oversoul…who are unafraid to hold a mirror up to the times that we live in…” This is certainly true. But first the seeking – best seen in its unselfconsciousness in the poem “Mystified”. Its opening lines are: “The truth is within us,/why then does it hide?/ O Lord.” In the racing pace of contemporary technologies, the witness emerges: “Sprouted, I split pea-like,/ half of me endeavors,/the other, observes.” A simple but revelatory solution flashes in the last verse: “Shall I reboot/and simply love you/like a child?/ O Lord.”

The poet knows the process involved in dealing with one’s shadow side. In “Shadows” these are “two-dimensional silhouettes,/devoid of mass or energy.//Companion to all,/friend to none.” Yet like flamenco dancers, they pirouette – not towards decline but skywards.

Not only are the poems compressed and pithy; they also make effective use of form. In “Vanishing Text”, the single verse flows like an inverted triangle, letting go of the moment, of the words… reaching the end word ‘nihility’. In “Black ‘n White”, we see once again a quality of letting go, of desirelessness at the end of the poem: ‘‘I attempt to write a poem/that will die on the page,/never giving birth to another.”

It is on the theme of illusion that we see both imagination and the apparently real at play. In “Illusions” based on the Moomal-Rano folktale, Queen Moomal, separated from her husband, Rano, grieves for him. Her sister, Soomal disguises herself as a man, and both simulate physical love. Rano mistakes Soomal for a lover and leaves – the simulation an illusion, the magical mirror shattering into a hundred pieces. In “Blind Vision”, illusion raises a question. Can a person in extreme poverty really believe ‘All is illusion’ as he limps across Haji Ali – hands red with rash, feet dark with dirt? “He taps twice,/earth responds;/he senses a black hole,/steps inside.” The reader wonders: Is the answer to yearning a dissolution of yearning?

The poet is well aware of the duality of pleasure and pain and their uncertainties. In “Dargah”, a couple prays for progeny at a saint’s shrine with a neem tree that has both sweet and bitter leaves. “He wonders:/ will the sweet leaf/make life bitter?//She wonders:/will the bitter leaf/make life sweet?”

In the prose poem “Fever Dream”, beneath flashes of disconnected thoughts, there is a breathless need to recuperate and not by fathoming daemon! Lying beneath the rotations of a fan, there is a yearning for the rest of dreamless sleep, when the mind and world dissolve into the bliss of unknowing:

Time ticks,

cats claw,

grow wings.

I fall asleep.

Closely related to the spiritual search are poems on love and death. In “Childhood’s Chase”, it is the present that is menacing – pleasurable like ‘a red and white candy bar’, baneful like ‘a cocktail of virulence’ – dualities latent ‘in the family mansion,/playing dead.’ In “Flight”, a love of long ago still lives in death: ‘and ants will carry me single file,/to that sacred place/where lovers still play/in long-forgotten ways.’ “Artifact”, one of Makhija’s most compelling poems, describes a portrait, hanging in a loft in a museum, that feels more alive than dead. Packed away in frames and polythene, it resembles a monk in saffron robes, terrifying for ‘the silence never wears off’. In a rare poem of what appears to be a deep personal loss, “Last Hours” written in couplet form, is not only about cancer, a wasting body and a tragedy that compels prayer on one’s knees. It raises a question: “Alone, with you, I think:/did he create death so we may not love?”

Well known for her plays which mirror our times, excerpts from three of Makhija’s plays feature in this book under the segment, Dramatic Verse. Being excerpts, the verses offer some interesting surreal and fantasy scenarios but feel incomplete and uneven. In “Meeting with Lord Yama”, Yama is to decide Brinda, a kindergarten teacher’s fate – whether she is to live or die. Yama asks what she has learnt from the four words: Love, Desire, Ambition and Hope. The poem dwells only on her response to love. Burnt by its inequities, Brinda sums it up in Shakesperean style: “To love the other is to forget oneself./But those who do live to regret./For while one forgets, the other feasts,/giving into temptation like a wild beast.” There is no mention of the other yardsticks: Desire, Ambition and Hope.

“The Last Train” has three ‘full-time schemers, part-time dreamers’ fantasizing riches through selling a people-proof door ‘to shut out friends, family and foes’ made from the unreasonable materials – plastic, Styrofoam, papier-mâché, resin – priced less than steel or teak! The question: While hilarious, how far can one sell dreams made from garbage?

Makhija’s real success lies in the way she presents grim social situations with a lightness of touch that is so matter of fact in its reality, that one can only doff one’s hat at her position as witness, as a fearless observer, who tells things as they are, without judgement. The settings are taken from Mumbai’s local trains, street corners, affluent homes, chawls et al, where glamour, greed, communalism, social and surreal situations depict life in a state of perpetual flux. Having associated with NGOs like Yusuf Meherally Centre, Aseema and Salaam Baalak Trust, Makhija mentions in her Author’s note, that her verse often reflects the experiences of vulnerable children, commodified brides and the displaced.

Humour underlies the grimness, almost as if the two need not be distinct. “Hiding in a night shelter” from the segment Minor Voices, is essentially a tragic situation when a girl pretends to be a boy just so she can live more safely in a shelter for boys, and not on the streets. She suffers from an anxiety at being found out: “I hate pants and shirts,/my boo-boos are showing.” And her plea in the end lines: “God, make me a boy,/please, make me a boy!”

From the same segment, one of the most compelling poems is “The Runaway”. The three voices of Child, Father and Stepmother have the power of a grim realism, all taken in one’s stride. Nothing is too shocking, for the reader must be shock-proof. “Who will fetch the water” is the dramatic line that reveals the minds of the three characters. In four staccato verses, everything is grist for the mill: child abuse, cruelty, filial indifference, filial distrust, communalism, opportunism and dreams of unfettered ambition.

One of the most daring poems, “Tara dialogues”, is not from a minor voice but from a Buddhist goddess – Tara – who is brought down to the level of a querulous brawling tribal woman, who, also named Tara, beseeches her for a child. The bait offered is restoration in society of the goddess’s forgotten identity – ‘reduced to a broken statue’. The Tara here is an antithesis of her otherwise compassionate nature, a venomous goddess who spouts invectives with glee: “I’ll peel your skin,/swallow your bones,/let blood spurt out of your veins,/deflate your lungs, bare your soul…./filthy as the dirt in your hut.” As predicted, the child born fair-skinned, also named Tara, drowns in a well at age one. The reduction through grim humor is complete in the last lines: “the villagers built a shrine/for the two who refused to let go/of life and death.”

The poem Black ‘n White, from her poetic phase 1995-2012, is dedicated to Dom Moraes. In it, it is Moraes who speaks to Makhija of her potential and talent: “your poetic voice is adventurous,/the chiselling will come with patience and age.” Makhija’s poetic voice is adventurous, and the chiselling has come with a wisdom that Makhija cherished in her grandmother who spoke to her of the aatman within: “Tumhare andar Bhagwan hai.” It is to her memory that this book is dedicated.

Bio:

Neera Kashyap is a writer of short fiction, poetry, essays and book reviews whose work has appeared in several international literary journals and anthologies. Her collection of short fiction is in the pipelines with Niyogi Books. A collection of poems is also scheduled for publication with Red River in 2025. Her book reviews have appeared in The Chakkar, Café Dissensus, Bangalore Review, Kitaab, RIC Journal, Different Truths & Hooghly Review.

***

Like Cafe Dissensus on Facebook. Follow Cafe Dissensus on Twitter. Follow Cafe Dissensus on Instagram.

Cafe Dissensus Everyday is the blog of Cafe Dissensus magazine, born in New York City and currently based in India. All materials on the site are protected under Creative Commons License.

***

Read the latest issue of Cafe Dissensus Magazine, “Epidermal Metaphors and Narratives in India”, edited by Elwin Susan John, Sophia College, Mumbai, India.