By Ananya Dutta Gupta

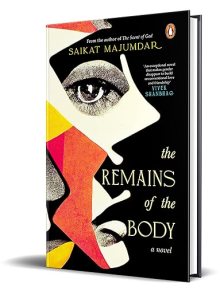

It is not enough to call Saikat Majumdar’s writing sensuous anymore. It was always already so, especially in The Scent of God (2019). In his latest, The Remains of the Body, his sensuousness has taken on a haptic intensity. Right from the start, the reader is placed almost within touching distance of his protagonist, whose gaze and touch in turn, more than voice, become their principal navigators through the rest of the book.

Majumdar’s fictional protagonists generally tend to be brooding, drifting loners at heart who go about their lives quietly. Even decisive changes in them come about without much ado and fuss. It is just that they have “gaping holes” for a heart. None more so than Kaustav in The Remains. The phrase does occur in the text (42), but the accompanying image of being trapped in a void suggests itself long before it is spelt out. The word “trapped” too occurs at least twice in the novel (16, 117). Expectedly then, The Remains ends on a note of thwarted epiphany rather than transformative closure. The protagonist persists in the irresolution and ennui of having to carry on living the familiar life.

The Remains is a kindly but unflattering portrayal of North American expatriate life, both on and off campus. Majumdar returns to vignettes of such lived experience more focally than in The Middle Finger (2022). The recurrence of the phrase “homecoming”, e.g. “a homecoming sort of love” (15) and “a little bit of a homecoming” (39), suggests a gerund of incompletion. Homecoming is forever an unfinished project, a flitting makeshift. For the small triangle of intimate friends meeting and parting alternately in California and Toronto, America remains the home of becoming, the home yet to become, constantly overshadowed by not so pleasant memories of the home they had grown up in and left behind in Calcutta. In this, The Remains, with its suitably deciduous title, would resonate with readers of Neel Mukherjee’s works of fiction, particularly Past Continuous (2008), except for the latter’s more seething, grating tragic pulse. Majumdar is perhaps deliberate in his avoidance of outright tragedy. Modernist fiction has a touch of disaffection and ambivalence that precludes tragic grandeur. As with Kaustav whose academic specialisation – urban homelessness – refracts his affective preoccupation with the idea of a home, interestingly, Saikat’s praxis as storyteller reveals elements from the literature of the modern, his area of scholarly research. Evidently, neither is willing to separate the academic and the affective too sharply.

Reading The Remains also found this reader remembering what at face value could not have been a more different story and context. Anuk Arudpragasam’s lyrically brutalist The Story of a Brief Marriage (2016) gives one the impression of being written from inside a body, with a sense of the surreality of being alive in the midst of war, of going about basic bodily functions – breathing, eating, bathing, waking up from sleep, defecating – with the smell of death all around all the time.

In comparison, Majumdar’s protagonists in The Remains lead safe and placid lives, far away from the precarity of ordinary men and women in times of war. The comparison, nevertheless, is in keeping the gaze firmly, unwaveringly, on “the language of the body”, a phrase used by none other than Majumdar’s narrator (122).

The Remains seems to affirm that to write about the body, one must write with it. There is thus a new fearlessness in Majumdar’s diction, a readiness to rip and strip his fiction of interiority of its Descartian burden. His narrator is no longer under any felt compulsion to match his protagonist’s diffident reticence by leaving things unspoken. The narrative texture is one of an urgency that leaks and seeps, instead of gushing. One must therefore stand really close to touch it – this silent Munch-ian scream – that sticks inside one’s mind.

In Keats and Embarrassment, Christopher Ricks relays a defining image of Keats handed down from Yeats via Lionel Trilling, namely of the poet as a young boy with his nose pressed against the window of a sweets shop (122). If one were to play Christopher Ricks to Majumdar’s narrator, The Remains would perhaps evoke the sensation of tropical sultriness, vestigial of Kolkata weather and at odds with the crisp air of California where the book’s present is set. The narrative is moored in an unresolved meteorological tension between tropical intimacies, cloying yet gritty, and the exigencies of the American Dream that each of the three principal persons is struggling to realise. That Dream, too, is more a legacy of their pasts, a construct that upper- and middle-class Calcuttans are yoked to very early on, than an aspiration produced by America in situ. The protagonist and his intimates are thus caught in a strange limbo, between a sticky past refusing to let go of their bodies even as their minds remain ambivalent about that looming, leaky shadow. It is a war waged over the body armed with its own cache of memories.

Two unrelated recent texts in the human sexual predicament, as it were, offer an interestingly varied dyad of comparisons with Majumdar’s language of representation. Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s posthumously published Until August (2024) is a remarkably adventurous exploration of female sexuality but its narrative is largely deflected on to the protagonist’s thoughts and actions either leading up to or ensuing from the sexual acts. The posthumous “Lost Novel”, as it subtitles itself, ultimately comes across as a wary testing ground for an emerging female gaze, emerging, that is, at an older time contemporary with Marquez himself. At the other end is Arna Mukhopadhyay’s Bangla adaptation of Shakespeare’s Othello, Athhoi (2024), where Shakespearean bawdy is reinvented as a tragedy of competing provincial lusts in the age of smartphones. Both Athhoi and The Remains enact the male gaze, though differently directed. Both brave the bawdy, as it were. Both negotiate an idiom that runs the risk of lapsing into Brobdingnagian grotesquerie. The balancing act in Athhoi entails deflecting the bawdy onto non-verbal innuendo, a figurative displacement seeking to replace visual lewdness. In The Remains, the challenge is inverse, namely, to arrive at a plainness that steers clear of periphrasis and prurience.

By marrying writing introspectively to writing through the body, Majumdar has gone all out to breach the opacity that all verbal art struggles with. At face value, the arbitrariness of the word as a signifier is far greater than that of a visual copy. A word has to work harder to become the thing in itself rather than the thing as imagined and mediated. Written language, that too when experienced through the printed word, fabricates the illusion of being a mental process that coopts the ocular into its field of operation. Writing the body, its sinews and synapses, the frisson between its own reflexes and impulses and the controlling force of the mind, is far more challenging than stream of consciousness. For language is always already in touch with strands of the mind, always already oblivious to that supreme machinery and manufacturer of intelligence, namely the human body.

In Majumdar’s poetics of truth, haptics is the litmus test. Thus, in The Remains, the mind is perpetually on a trial by the body, and the body never lies. It is just that the two men whose deep and indefinable bond is soldered in mutual wariness rather than trusting disclosure refuse to live by that truth.

Ultimately, the queerness of The Remains is in the refusal to limit the gaze to a gendered function. It seeks to liberate the male gaze from the stigma of crass objectification, what the narrator calls “male bawdiness” (98). The narrator injects back into that gaze a tenderness and a desiderium that the world does not readily cognise as an attribute of the male writer.

When she says, “writing is woman’s” (42), Héléne Cixous famously designates the ability to embrace a multitude of selves as a feminine attribute. To quote at length,

If there is a self proper to woman, paradoxically it is her capacity to depropriate herself without self-interest: endless body, without “end,” without principal “parts”; if she is a whole, it is a whole made up of parts that are wholes, not simple, partial objects but varied entirety, moving and boundless change (44).

Saikat Majumdar’s The Remains of the Body suggests a decisive move in the author towards écriture feminine.

Works Cited

Arudpragasam, Anuk. The Story of a Brief Marriage. New Delhi: Harper Collins, 2016.

Atthoi. Directed by Arna Mukhopadhyay, performances by Arna Mukhopadhyay, Anirban Bhattacharya and Sohini Sarkar, Jio Studios and SVF Entertainment, 2024.

Cixous, Hélène. The Hélène Cixous Reader. With a preface by Hélène Cixous and foreword by Jacques Derrida. Edited by Susan Sellers. London: Routledge, 1994.

Majumdar, Saikat. The Remains of the Body. Gurugram: Penguin, 2024.

Marquez, Gabriel Garcia. Until August. The Lost Novel. Translated by Ann McLean. UK: Viking, 2024.

Ricks, Christopher. Keats and Embarrassment. London: Oxford University Press, 1974; paperback 1976.

Bio:

Ananya Dutta Gupta teaches English Literature at Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan, and writes scholarly articles, essays, and poetry. An earlier essay of hers on Saikat Majumdar’s fiction may be read online at Café Dissensus Every Day.

***

Like Cafe Dissensus on Facebook. Follow Cafe Dissensus on Twitter. Follow Cafe Dissensus on Instagram.

Cafe Dissensus Everyday is the blog of Cafe Dissensus magazine, born in New York City and currently based in India. All materials on the site are protected under Creative Commons License.

***

Read the latest issue of Cafe Dissensus Magazine, “Epidermal Metaphors and Narratives in India”, edited by Elwin Susan John, Sophia College, Mumbai, India.