By Sreemati Mukherjee

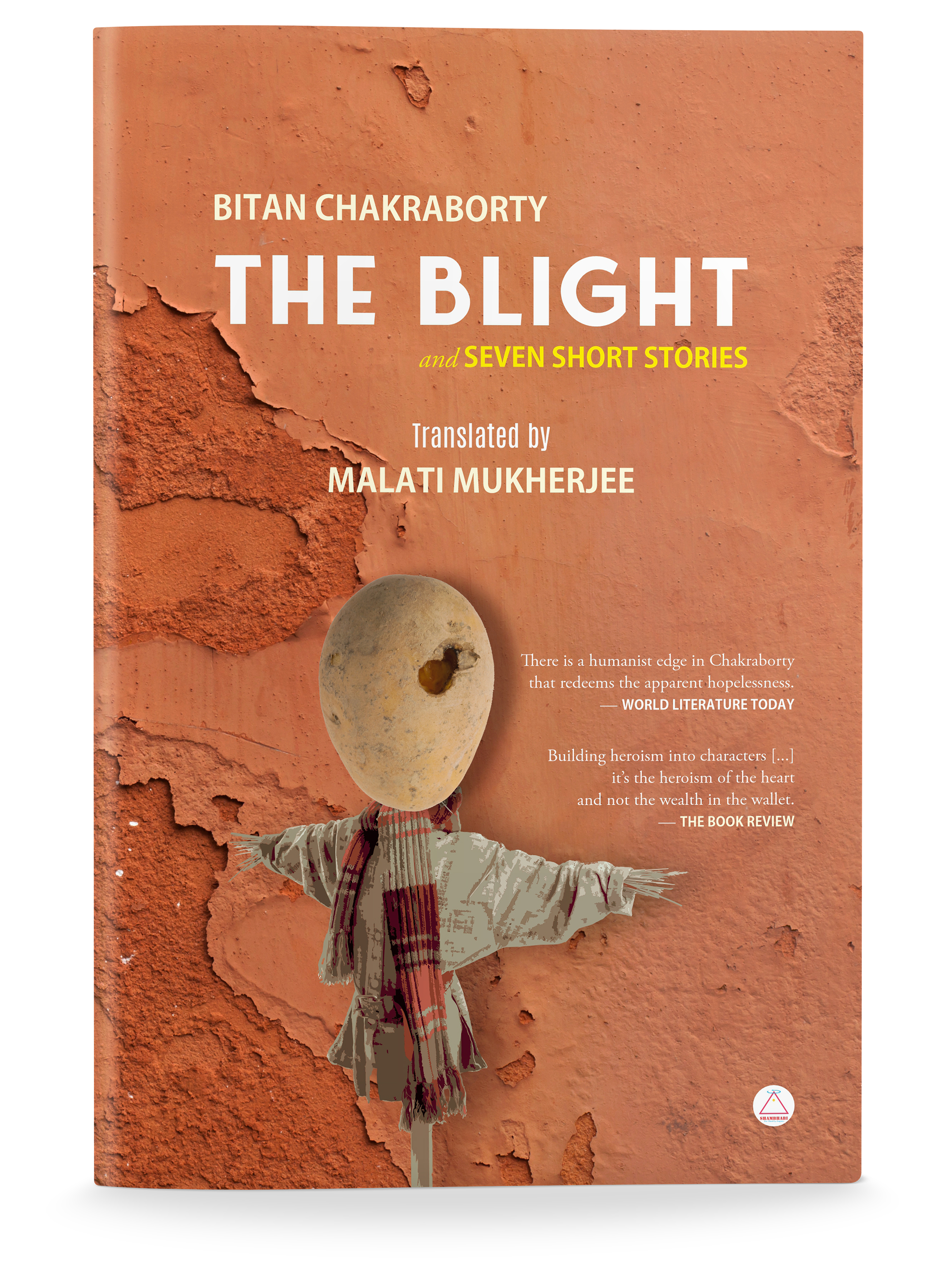

Bitan Chakraborty’s The Blight and Seven Short Stories, originally written in Bangla and translated into English by Malati Mukherjee, is a wonderful collection of stories, which may tease the term “short story” a bit. “The Blight” is a novelette. I will begin with this remarkable piece of imaginative fantasy with its close dialogic relationship with the hard contours of the real world.

“The Blight” throws up several meaningful strands. On the one hand, we have the protagonist (I prefer to see him as the main character and not his son, Ashesh) with his keen sympathy for the vegetable world, and one of its most humdrum members, the potato. The potato is the most accessible vegetable for Moni’s very meagre food budget. Hence, he may look with attention at the fresh vegetables lined up in a shop window in the local market, but it is the Chandramukhi potato, whose price he will ask the vendor, and ultimately buy. In fact, as his son Ashesh bitterly reflects at some point in the story, all Moni understood about the diet or fare his family needed was rice and vegetables daily and fish occasionally. However, what surfaces later in a rather Gothic manner in the text is Moni’s abnormal fascination for the potato, his fantasies about its possible extinction in the hands of black marketeers, the need to look for a medicine that will heal the wound of his imaginary potato mountain and his own desire for refuge within this wound. A version of Tzvetan Todorov’s uncanny and the marvellous surfaces here. However, counterpointing the uncanny and the marvellous, are also the strong realistic elements of the plot where the underworld of construction activities and neighbourhood politics are portrayed to chilling perfection.

Most of the stories have a dark strain to them. Violence, despair, and lack of fulfilment seem to be key issues that power their plots. “The Landmark” is an example. In this psychologically resonant story, the complexes of a young man towards a friend who has done well are brought out. Although the terms of their relationship seem sound, Tapan, the protagonist, is unwilling to meet his friend Jashar who has ‘made it’ as a successful teacher in a college. Despite several inhibitions, he still tries to make it to Jashar’s house in Ghaziabad; however, his phone blanks out due to lack of sufficient charge, and he cannot remember the landmark that Jashar had mentioned to him, and he ultimately does not show up at Jashar’s house. Chakraborty is subtle enough not to indicate whether Tapan is relieved that the meeting did not take place. Visibly, at least, he seems to have no regret.

“The Spectacles” is rather ominous. One picks up negative vibrations from the very beginning; something wrong about Siddharth taking the wrong turn. Many of the stories evoke a feeling of matters gone awry and a sense of impending doom. As Siddharth gets ready to go to Sameer-da’s house, I remember the quote from Macbeth (Act 4, scene 1) where one of the witches cries out, “By the pricking of my thumbs/something evil this way comes.” This story has an intense interface of theatre, youth, sand and stone chip business, state politics, and the Left in Bengal, being implicated. Siddharth’s father had originally owned the brick, sand and stone chip business, and he had managed to remain a more or less clean businessman. He had had a relationship with the local Syndicate but had not allowed unfair politics to eat into his soul. Siddharth, however, fails. He lets down Molly-di and Sameer-da, who had lovingly nurtured his taste in theatre. When they needed help from the local goons who were making trouble because Sameer was not buying sand and stone from them, Siddharth did not lend them his support. Siddharth was once linked to theatre just as the Left Front government had had close ties with the IPTA and street theatre. He had played the role of the innocent Amal in Tagore’s Dak Ghar (The Post Office). The spectacles are a key leitmotif here. There is something wrong with Siddharth’s new spectacles – ‘new’ also implicating his new being, ruthlessly cut off from those who had nurtured him and helped him grow as an artist. Siddharth’s inability to see clearly and his blinding headache chillingly recall Gloucester’s confession in Act 4, Scene 1 of King Lear: “I stumbled when I saw.”

In practically every story, there is a narrative of human greed that has gone awry; of innocence corrupted by the real world; of the inability of the human being, usually all male in this collection of stories, to retain idealism and incorruptibility. Darkness and death, politics and the stone chip business, the losing of youthful idealism to a life of pure self-interest and ruthlessness, and a pursuit of culture that ends in the loss of youthful ideals to political exigency are some of the strains that run through Chakraborty’s fiction. In his book Reading for the Plot: Design and Intention in Narrative (Harvard University Press 1992), Peter Brooks uses the term “narrative desire” to explain the undercurrent of an author’s own predilections in telling a story. If there is “narrative desire” in Chakraborty, it seems to be a fascination with death, violence and infidelity.

Another story that has a chilling resonance is “The Site.” Chakraborty’s stories are also about the paradoxical nature of power. Nalinaksh, the protagonist of “The Site,” has reached where he wanted at age 45. From his apartment in a city high, the beggars he sees on the streets give him a curious sense of self-gratification. Chakraborty is astute in reading human characters – he is able to realize in full dramatic connotations jealousy and self-aggrandisement in his portrayal of characters. However, there is a beggar who stubbornly sits on the street just opposite Nalinaksh’s apartment; he seems to want to say something. Nalinaksh has some strange fascination for this beggar. Almost as though he is his alter-ego, representing that fall from grace that Nalinaksh somehow still feared for himself. Like in “The Landmark,” where no success is enough to give Tapan a sense of security, Nalinaksh is too conscious of his victory, his ability to have triumphed over failure and not having enough. As a counterpoint to his own power fantasies are those of his son Neeladri, who is suspicious of his father giving more opportunity to Neeladri’s ex-girlfriend Tanuja. Hari, the servant, is also on Neeladri’s side. At the end of the story, as Nalinaksh bends down to see the beggar clearly, he is pushed from behind. Once again, the story of father-son rivalry replicates itself.

Malati Mukherjee has done a splendid job of translating the stories. Her prose is supple, unpretentious, and pleasant to read.

Note: In his essay “The Uncanny and the Marvellous,” Tzvetan Todorov explains that the uncanny and the marvellous are both species of the fantastic in literature. Contemporary Literary Criticism. Eds. Robert Con Davis and Ronald Schleifer. New York and London: Longman. 1989. 175-184.

Bio:

Sreemati Mukherjee, Professor, Department of Performing Arts, Presidency University. Areas of academic competence are Feminist theory and criticism, postcolinial literature and theory, narrative studies, performance studies. Latest books are Women and the Romance of the Word: 19th Century Contexts in Bengal (Bloomsbury) and The Many Dialogues of the Sri Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita (Hawakal), a Bakhtinian study of this iconic text.

***

Like Cafe Dissensus on Facebook. Follow Cafe Dissensus on Twitter.

Cafe Dissensus Everyday is the blog of Cafe Dissensus magazine, born in New York City and currently based in India. All materials on the site are protected under Creative Commons License.

***

Read the latest issue of Cafe Dissensus Magazine, “The Other Mothers: Imagining Motherhood Differently”, edited by Paromita Sengupta, Director of Studies in Griffith College Limerick, Ireland.