By Jagari Mukherjee

The Buddha has been an intriguing figure in religion and folklore down the centuries. In the twentieth century, novels such as the German Siddhartha (1922) by Herman Hesse, and the Keanu Reeves-starrer movie Little Buddha (1993) revolve around the Buddha and speak volumes of the world’s fascination with him. The Flower Power generation of the 1960s and the Beat Poets were influenced by Buddhism.

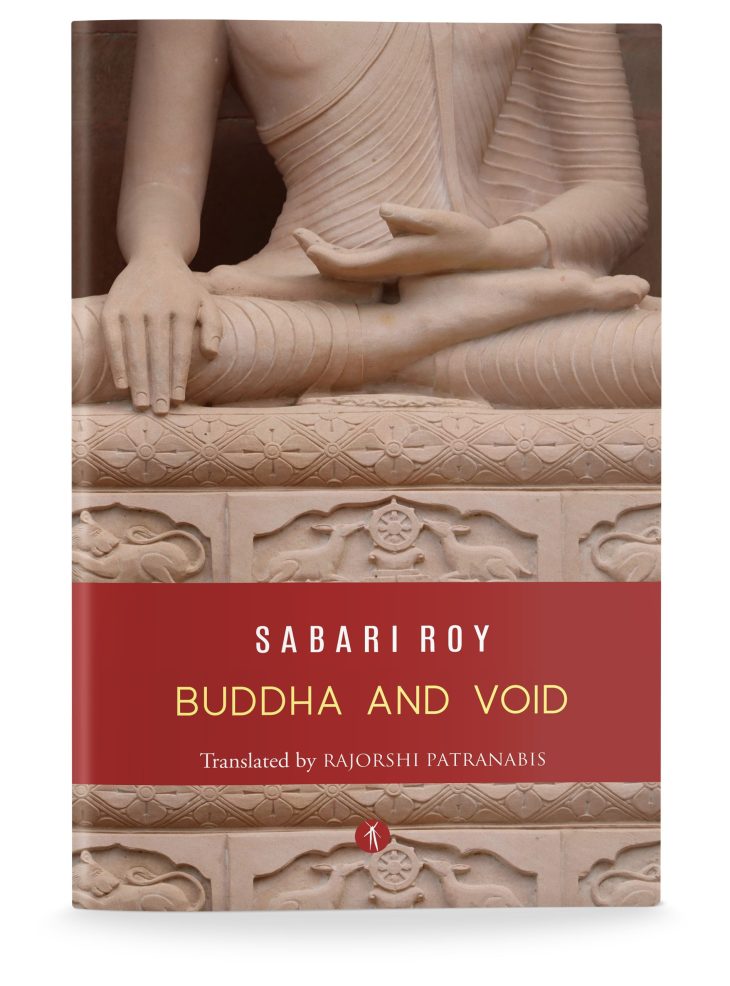

Pondering on Sabari Roy’s Buddha and Void, a collection of poems, as translated from the original Bengali by Rajorshi Patranabis, I am compelled to think about the void, the shunya, the zero, the lack, and what it stands for. To me, it symbolizes both emptiness and fulfilment, as zero is a full circle. I remember watching a bilingual British Indian production, back in 2006, of Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing at David Sassoon Library in Mumbai. In the feminist interpretation of the play, the word “nothing” was taken to mean a void related to a lack in the woman’s body as compared to a man’s. In the present collection of poems, the void is spiritual rather than physical, yet it is ironically symbolic of the physical absence of the beloved and the metaphysical love that ensures a presence in the lover’s thoughts and reminiscences.

The void is a circle depicting wholeness. The circle as a shape has myriad religious connotations. In Christianity, it appears as a halo, whereas in Eastern traditions, it is a mandala. In the golden world depicted in Ancient Greece, a circle becomes a wreath around the head of a lover or a wreath of laurels around the head of the Poet Laureate. On the other hand, the cross is popularly a Christian symbol, representing, among other things, the pain and suffering that we undergo in our mortal lives. One may take the very first poem of the book as a search to overcome suffering through spirituality:

The body is

full of crosses

and circles.

Glass top reflects

age and sickness;

intoxication and healing.

Just the two to offer:

Buddha and the void. (Page 17)

The transformation of the handsome, rich, worldly young Prince Siddhartha to Gautama Buddha is a well-known story. The narrator gives it a contemporary twist, where Siddhartha is set up as an example for us to emulate. Before disseminating the message of peace in the world, Siddhartha must find it within himself.

Man doesn’t need to know

the airport where

Siddhartha loses His luggage of desire.

He does not have clothes to change;

the lost box had all the sickness, suffering and

death.

From dawn to evening,

The sky is pristine.

His tryst with peace;

the twilight is smeared with saffron dust. (Page 22)

I’ve always maintained that the translator, Rajorshi Patranabis, is essentially a poet of love, and despite my initial idea that it would be a rather dry philosophical masterpiece, I discovered that it is a paean to love. The poems in the book are painted with enamels of soft colors. Each layer uncovers and reveals a hidden gem. One can read the poems as the personal prayers of a seeker addressed to the Buddha, but one can also read these as poems of love, of sublime yearning that Yashodhara had for her Siddhartha, or Radha cherished for her Krishna. There is the pain of separation at the earthly level but ecstatic bliss in the knowledge that the beloved is spiritually never absent and is a part and parcel of the lover. Let me illustrate this with a poem:

Separation sings of zero.

Zeroes on the left are useless.

The heart is a lotus bud.

The zero merges with the song.

The difference between zero and zero is

separation.

Quotient of the torn lotus petals is zero.

Union amidst hard-hitting waves

leads to zero.

Zero is an excuse, directionless, aimless—

bubbles of void complete the zero. (Page 34)

Yet, love, however profound, is often entwined with lust, and the craving for the physical body makes the lover/narrator restless. Yashodhara remembers a time when the Buddha was her young husband, Siddhartha, and she longed for a return to her youthful days of passion.

You come back to return.

From a seed to a tree,

and tree to seeds,

love suffers the lustful aroma

of the present time.

You were there before Buddha,

you still exist.

Through past and future,

sorrows of the self

touch our hearts. (Page 32)

As the poems progress, a story emerges, woven like a tapestry. The narrator’s emotions mature and ripen, and physical desire is sublimated into the metaphysical. The narrator achieves the calmness of wisdom and finds fulfilment in nirvana after traversing the path of both sensual and metaphysical love.

There is no shape or area,

neither taste nor flavor, color or nectar—

easy equation of relationships

flow with the water of wisdom.

I move away from the ground—

from the banks.

It is not gene, color, or knowledge

but attributes and austerity.

Wisdom emanates from virtues.

The virtues house wisdom. (Page 68)

The next poem reminds me of what Sigmund Freud had said about altruism as recorded by his students in the book, Introductory Lectures in Psychoanalysis (1891). According to Freud, when a person’s love radiates and encompasses the other person, and through that world, it is altruism.

Is zero round, square, or hexagon?

Is it black or white, light or dark?

Who plays there? Which game

will you play with the limbs,

head and body of zero?

Will our world ever remain divided,

and we, oblivious and unconscious? (Page 69)

Love, in all its shades, is what most beautiful poetry is composed of. Freud takes an example from Goethe’s West-Eastern Diwan to illustrate what he thinks is true love. He excerpts a conversation between two characters, Hatem and Zuleika. While Zuleika is self-centered and cares only for her own fulfilment, Hatem has quite a different take:

So it is said, so well may be,

But down a different path I come:

Of all the bliss earth holds for me,

I in Zuleika find the sum.

Does she expend her being on me,

Myself grows to myself of cost;

Turns she away, and instantly

I to my very self am lost.

(The piece above is excerpted from Ernest Dowden’s English translation of Goethe’s West-Eastern Diwan, which in turn is a translation of Persian poet Hafez’s Diwan.)

Thus, the ‘sum’ means a fulfillment, a circle, or a zero. To lose something or someone is to leave a void. The Buddha in Buddha and Void is the symbol and metaphor of true love – a lotus blooming in the hidden depths of the lover’s soul.

Bio:

The winner of the 2019 Reuel International Prize for Poetry, Jagari Mukherjee is the Founder and Chief Executive Editor of the literary journal, EKL Review, and the Editor-in-Chief of Narrow Road. She has authored five solo collections of poetry – two chapbooks and three full-length volumes. Her most recent publication is Exit Noire by Bookwryter. She has won numerous prestigious awards, including the Rabindranath Tagore Literary Prize for Book Review (2018), the Women Empowered Gifted Poet Award (2020), the Jury Prize at Friendswood Library’s Ekphrastic Poetry Reading and Contest (2021), and most recently, The Bharat International Award for Literature 2022 for Short Story. Her book, The Elegant Nobody, published by Hawakal, was shortlisted for the prestigious Tagore Prize in 2022.

***

Like Cafe Dissensus on Facebook. Follow Cafe Dissensus on Twitter.

Cafe Dissensus Everyday is the blog of Cafe Dissensus magazine, born in New York City and currently based in India. All materials on the site are protected under Creative Commons License.

***

Read the latest issue of Cafe Dissensus Magazine, “The Other Mothers: Imagining Motherhood Differently”, edited by Paromita Sengupta, Director of Studies in Griffith College Limerick, Ireland.