By Mohammad Asim Siddiqui

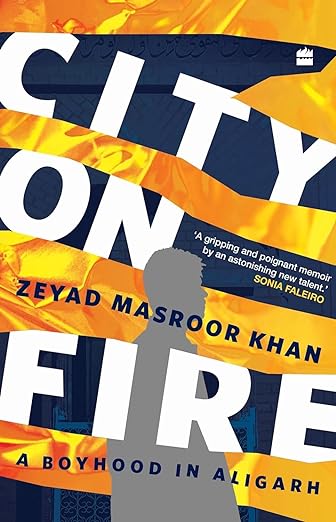

I have been living in Aligarh for more than four decades, but I discovered a major part of Aligarh from Zeyad Masroor Khan’s coming of age memoir City on Fire: A Boyhood in Aligarh. A resident of Uper Coat, a relatively better-known Muslim ghetto, ‘(mis)pronounced’ as Upper Coat by Aligarh residents of the Civil Lines area, Khan also knows other Muslim ghettos of the city like Bhujipura, Nuner Gate, Babri Mandi, Mian Ki Sarai, Thakurwali Gali, Haddi Godam, Sarai Sultani and Shah Jamal inside out to debunk many myths about them. Considered as scenes of crime, squalor and iniquity not only by the majority community in Aligarh, Aligarh Muslim University people, a majority of them Muslims, are no less guilty in forming unfounded notions about these ghettos. Thoughtfully titled, the word fire in the title of the book captures the riot-prone history of Aligarh and the volatile nature of peace that exists in the town. “Fire reminded me of the violence I witnessed in Aligarh, the Delhi riots and many acts of violence against Muslims that adorned newspapers. It sparked my deepest fears,” writes Khan.

Aligarh’s history of riots has been documented in some well-known studies which include Paul Brass’s The Production of Hindu Muslim Violence and the Indian State (2003). Ashutosh Varshney’s Ethnic Conflict and Civic Life: Hindus and Muslims in India (2002) lists Aligarh as one of the seven cities which have witnessed 49 percent of all urban deaths in communal violence after independence. Aligarh has also found a worthy mention in many recent memoirs penned by writers having some association with Aligarh. Naseeruddin Shah, an alumnus of AMU, wrote a chapter on ‘Aligarh University Absurdists’ in his excellently-written memoir And Then One Day (2014). His brother Zameer Uddin Shah, vice chancellor of AMU from 2012 to 2017, talked about his efforts to make AMU a top-ranked university and his spats with some political leaders during his tenure in his memoir The Sarkari Mussalman (2018). Muzaffar Ali credits AMU’s poetic culture and its celebrated Urdu poets for influencing his visualization of subjects in his films in his autobiography Zikr: In the Light and Shade of Time (2023).

However, in all these memoirs Aligarh city, leave alone its Muslim localities, is completely absent. Even Iqbal A. Ansari, a human rights activist and a professor of English at Aligarh Muslim University, has not included any chapter on riots in Aligarh in his edited book Communal Riots: The State and Law in India (1997). The city with its real people who think, feel and behave like any one of us is also absent in various Urdu memoirs which never tire of glorifying Aligarh. City on Fire fills this gap. Though there are two interesting chapters in the book devoted to Aligarh Muslim University – the street lingo of the campus, ‘ground rules of Aligarh badmashi’ and the author’s exposure to classic English and European fiction making for interesting reading in these chapters – City on Fire captures not only the fears and uncertainties in Muslim ghettos but also the dreams and aspirations of many young men and women who love English comics and pursue their education wondering about the absence of hospitals, ATMs and schools in Muslim ghettos and the exclusion of Muslims from comic book characters. Khan loved Dhruva, a character in Raj Comics, but noted that “there were no Muslims in Dhruva’s world, except Karim, one of the cadets in his commando force.”

Khan’s was an area full of open drains where “an average of four balls in every over end up in drains”, where educated parents warn their sons, “kids who don’t study end up as karkhaanewale” and where “go to Pakistan” was a regular jibe thrown at people going to attend their Friday prayers. Ironically as a kid the author was happy whenever there were riots because “it meant not going to school” and “violence was just another neighbour.” Remembering events in his life clearly since 1994, he not only witnessed violence, felt the communal tension which was “a part of our existence” and lived through the experience of riots, he also writes in his memoir many accounts of riots heard from his elders in the family. The memoir also records influence of family, school and popular culture in shaping his life. He was fixated on animal shows on Discovery Channel and “Saas Bhi Kabhi Bahu Thi”, a popular soap of the 1990s, and had a dream of making it to “Kaun Banega Crorepati”. Loving effect, Khan learnt Gayatri Mantra from SBKBT and used to recite it “to shocked friends and appreciative Hindi teachers”.

Divided in three parts – childhood, boyhood and adulthood – the City on Fire captures a consciousness of riot reflected not only in various incidents described by the author but also in his choice of original similes like “Lalu’s rickshaw was as crowded as a hospital after a riot” or “ Burning in anger like shops did during riots.” There are other novel similes in the book which show the author’s keen observation of patterns of Muslim lives: “The bus was as quiet as a mosque in Asr prayers”; “Denial is like an old beggar sitting outside a mosque. You don’t see him because you don’t want to”; “Softness in her voice vanished as swiftly as madrasa kids after their lessons.” Khan’s house Farsh Manzil (a lot of Aligarh’s houses, even small ones, have a ‘Manzil’ in their names) which connects a Hindu and a Muslim ghetto and has been a permanent site of tension provided the author a vantage point to see the entire anatomy of a communal riot: feeling the tension in the air, judging the danger, confronting an angry mob or finding an escape route through many secret staircases in the narrow lanes of his locality. The author describes how an electric switch was there in many homes which was used to light a bulb on the terrace to indicate the danger of an attack on their homes. His love of comics in his childhood took him to many Hindu localities like Gudiya Bagh “the biggest risk of my life”, later learning from his mother that the demography of Gudiya Bagh, a mixed neighborhood where her mother had a big home once, completely changed after a riot.

Poignant and painful narratives of the victims of communal violence – Azim, Uzma, Yasin, Shadab and many others – come alive in the book to show the horror and ubiquity of communal violence. “Spatial distance and reason” had no role in the outbreak of violence as a riot happening in faraway place like Gujarat in 2002 would result in a random killing of Samiullah on Railway Road in Aligarh. Noorjahan Apa, the author’s tenant for decades, once fought a lone battle against an angry mob trying to enter Farsh Manzil. Written with honesty and candour, it is basically the Muslim side of the story that the book recounts. However, the book is not lacking in highlighting many Hindu heroes like Bablu, a Hindu, who saves a school bus carrying Muslim school children and teachers from a group of Hindu rioters.

Khan connects his personal narrative with the larger ideological forces and the political events that have changed India’s character in the last few decades. All national and international political events – demolition of Babri Masjid, 9/11 and America’s attack on Afghanistan, Gujarat riots and protests over CAA – have affected life in his city and locality leaving their mark on his growing consciousness. From his ‘fundamentalist phase’ in school when he would take issues with his schoolmates and teachers over issues of Muslim identity to his mature phase in Delhi during his career as a journalist when he was naively secure in his belief that he has left his memory of riots in Aligarh, the book covers a large canvas. He narrates an incident how he was beaten up by the Father in his convent school for greeting him with ‘As-Salam-Alaikum’, an incident “which did not stop me from being the face of Muslim assertiveness at St Fidelis.” Later like many other Muslims, “every time I heard of a terror attack, I’d pray for the attackers to not be Muslim.” The author’s ruminations over loaded words like Partition, abandonment, mob, memory, migration, fire and hate and their historical resonance also connect his personal story to larger historical and philosophical developments.

However, despite the gloom that pervades the memoir, the book evinces some hope at the end. This reviewer is not sure if this hope is real or it is a narrative device to end the memoir with a happy ending. Echoing Rahi Masoom Raza’s love for his village Gangauli and his resolve not to leave his place, Khan’s father, who refused to migrate to any other country because “it (India) is my home, how could I ever live if I left my home”, becomes a source of inspiration for the author in his dark moods. Realizing that he would also never leave Aligarh, the author also realizes that “I was now turning into my father.”

Bio:

Mohammad Asim Siddiqui is Professor in the Department of English at Aligarh Muslim University.

***

Like Cafe Dissensus on Facebook. Follow Cafe Dissensus on Twitter.

Cafe Dissensus Everyday is the blog of Cafe Dissensus magazine, born in New York City and currently based in India. All materials on the site are protected under Creative Commons License.

***

Read the latest issue of Cafe Dissensus Magazine, “The Other Mothers: Imagining Motherhood Differently”, edited by Paromita Sengupta, Director of Studies in Griffith College Limerick, Ireland.

Appears to be an interesting book from the detailed review capturing how Aligarh, the city is portrayed in the book. Upper Court is generally absent from any significant mention as noted by Prof Siddiqui in books written on Aligarh as their focus is mostly on the life at AMU or Aligarh as a city of recurrent roits. City of Fire turns upper court, a muslim ghetoo live on its pages and records in minute details through the protagonist his aspirations and fears spread over three decades. It would be an interesting reading for those who want to see how growing up in a locality marked by communal roits leave a life long impression on one’s psyche and shake one’s confidence and in turn may have a bearing on all his future affairs.

A nice review which invites the readers to grab the book.

LikeLike

I must congratulate Zeyad Khan for giving us a unique and detailed personal perspective on the city of Aligarh which throughout my memory, too, has been a source of constant fear of communal violence. I also congratulate the author on getting his memoir reviewed by one of the most insightful, avid, and voracious readers, and reliable, honest, and encouraging reviewers in India, Professor Asim Siddiqi.

The review effectively captures the essence of the book and provides a comprehensive analysis of the memoir highlighting key themes, the author’s narrative style, and the significance of the book. The author’s exploration of Aligarh’s hidden facets, emphasizing the importance of his work in filling the gap in literary representations of the city, has been convincingly highlighted.

The commentary also gives us a clear picture of the author’s skillful debunking of myths surrounding Muslim ghettos, vivid descriptions of his early life, and the powerful portrayal of communal tensions and its impact of political events in the city, all showcase the reviewer’s thoughtful engagement with the content.

I thoroughly enjoyed the reviewer talking about Khan’s use of original similes that provides a glimpse into his observational skills. The acknowledgment of the memoir’s depiction of both despair and hope, and its connection to broader historical and philosophical developments, contributes to a well-rounded evaluation.

In short, the review is a convincing piece of literary criticism that effectively conveys the strengths of “City on Fire,” and it manages to motivate even a reluctant reader like me to acquire a copy of the memoir promptly, and read it too.

LikeLike

The review certainly encapsulates the essence of the harrowing, personal,psychiatric narrative of all those victims of the envisioned trauma in the post communal feudes that has tattered the very fabric of Aligardh composition which could otherwise have been known only for its premier world class seat of learning(AMU)that I have been longing for no substantial reasons so far except hobnobbing with some finest minds around me like Dr. Asim Sb,Dr Mobin Sb,leaving an indelible mark.

Any memoir mesmerised in any form of narrative,unravelling the inner core of chain of thought processes with the experiential accounts would remain completely a diatribe,unless it sways to stray into the wider realms of human universal tumultuous landscapes as the communal feuds,riots,violence,Hindutva orgies have never been the prerogatives of paltry ghettos as mentioned and the communal flares have been brewing up for ages across India,never to be nipped in the bud.The worst imagined fear of my life has been the traumatic snippets, being aired or filmed through Hindi cinema which has served to aggravate the fear syndrome as the victims are always from one community and that too at the behest of the people in governance. Having just an iota of preliminary impression of the memoir through the carefully crafted review here, I could only form a prognostic,impressionistic and perhaps opinionated view of the memoir as the proof of the pudding is to be uncovered.

Wishing the writer and the reviewer a brilliant score on the card!!!

LikeLike