By Ashish Dwivedi

The 1930s was a monumental period in the history of Indian film; not only filmmakers and producers were attempting to navigate the structure of filmic language in India – initially blueprinted through Alam Ara[i] – but were also redefining the genric preference of audiences by essaying “the social film”, aligning films within austerity, contemporary relevance, and a vision of new modernity. Ergo it’s not surprising that the 30s became witness to reformative and daring narratives, considerably produced by two rising studios: New Theatres of Calcutta and the Bombay Talkies. In the wake of new realist cinema, older studios like the Prabhat Film Company must have recognised the urgency to unclench itself from the hold of mythologicals and costume dramas, a genre in which Prabhat seemed to excel with pioneering works like Sant Tukaram (1936), Amrit Manthan (1934), and Sairandhri (1933) under its copyright. Therefore, an emerging wave of Prabhat productions heralded the rise of socially-informed, humanitarian, almost-radical films like Amar Jyoti (1936), Aadmi (1939), and Padosi (1941) – before these thoughts were extended through V. Shantaram’s Rajkamal Kalamandir and its daring newness.

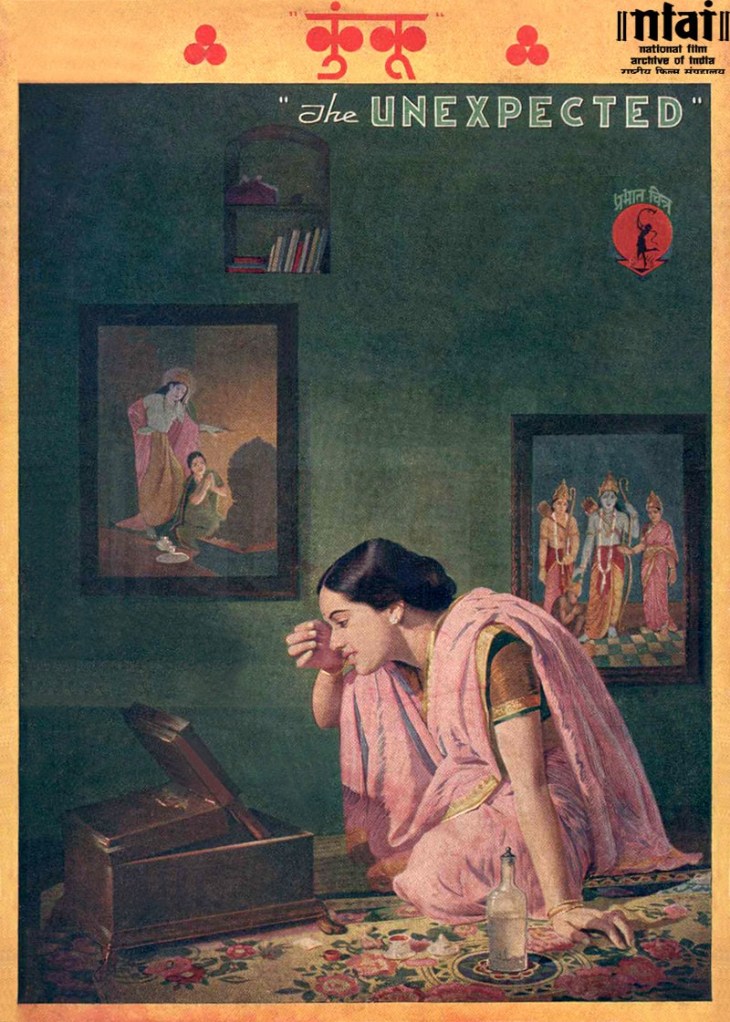

The name of V. Shantaram has been always associated with unconventionality and unorthodox values – thanks to Baburao Patel’s earlier appraisal of his films in filmindia – and, certainly, his passion for literary adaptations. The latter-most aspect is, indeed, minimalist in light of his oeuvre, but some of his greater works – Sinhagad (1933), Shakuntala (1943), and Dr Kotnis Ki Amar Kahani (1946) – are founded upon classical works. Another one being Kunku, a.k.a. Duniya Na Mane (1937). Based on Narayan Hari Apte’s novel, Na Patnari Goshta, the film is not only deemed one of the sharpest critiques of women’s debilitating condition(s) in pre-1947 India, but also one of the earliest examples of proto-feminism and ideological subversion. I’m suspecting that ideological subversion was one of V. Shantaram’s auteurist signatures; we often discern that in his introductions of radical concepts like female piracy (Amar Jyoti) or reformist prison (Do Aankhen, Barah Haath), but his handling of Shanta Apte’s unflinching, unbending character-arc in Duniya Na Mane is just a notch above others, always more memorable and striking, more defiant. Naturally, the film falls within the furrow of cultism and Apte’s stardom – and this makes it unfathomable for Duniya Na Mane to be read along distinctive, albeit more timeless, perspectives. However, thanks to the advancements made in modern literary criticism that a parallel, alternative reading of this classic seems plausible. The Derridean philosophy of deconstruction, and the critical standpoint of Wimsatt and Beardsley about intentional fallacy, proffers us the opportunity to re-view Duniya Na Mane beyond feminist ideas of exploitations and empowerment, and into the quagmire of neurosis, mental health, and geriatric complexes.

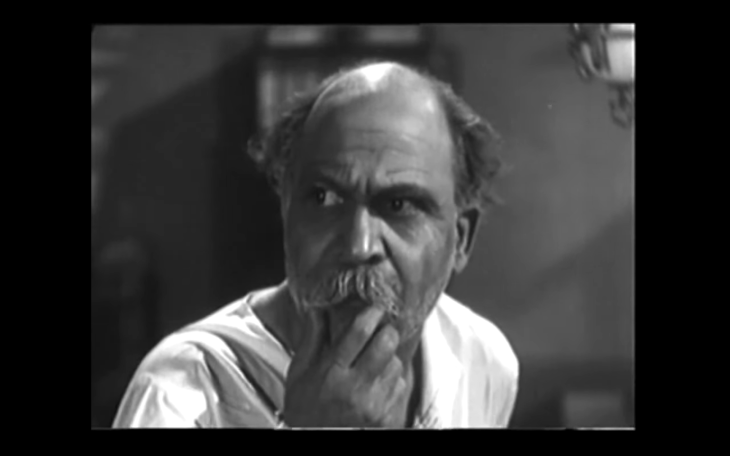

Awakened by a techno-sociological undercurrent that proactively represents mental health and geriatric concerns – which has presented India with some gripping narratives like Qala (2022) and 102 Not Out (2018) – the 21st century viewer of Duniya Na Mane might be more inclined towards empathising with Kaka Saheb and his psychological ruin due to (1) his complexes of being called “old” and (2) societal questioning of his recent marital alliance to a comparatively younger woman, if not completely ignore the film’s feminist overtones. The film problematises the landscape of unmatched “holy matrimony” against the cost of depriving Kaka Saheb of any potential humanity – and subsequently exposing him to a vulnerable boiling point – and deploying his character to lopsidedly serve karmic interests. Cinematic motifs of a broken wall-clock and a barren garden further precipitate the film’s engagement with the notion of old age; and while the symbolism of the barren garden may have been twofold – the garden was later restored to its former glory by Nirmala (Apte’s character) and therefore could be re-viewed as connotating Saheb’s return to marital bliss – it’s the wall-clock that bears the brunt of absolute symbolic destruction. It seems Duniya Na Mane deliberately stages the significant episodes of Saheb’s deterioration, keeping the wall-clock as a single witness to his emotional tragedies.

I suspect it would be more reasonable to analyse Duniya Na Mane as a story of Kaka Saheb if analysed in relation to the character of Nirmala and her situational or contextual social realities. The story of the film unfolds years before the lawful enactment of the Hindu Marriage Act ’55, and thereby Nirmala – at the forefront of law – was naturally deprived of her right to divorce. Her entrapment is later modified as “acceptance of fate” and the film pursues that through the musical piece, “Kyun Dukh Mein Samay Sab Khota Hai”, insisting a worn-down Nirmala to finally accept the reality of her marriage to Kaka Saheb. Furthermore, it’s intriguing that while Nirmala maintains her onslaught against her in-laws, in her attempt to display her resentment against her unjustified marriage, the film ultimately pictures her a traditional, God-fearing wife, who respects her wifehood – symbolically illustrated through the significance she bestows on her sindoor. Speaking of this nuance reminds me of the film’s climax when Kaka Saheb effaces her sindoor from her forehead, and the pathos-evocative monologue that follows when Nirmala wonders over her status of liminality as wife/widow. That episode enables us the contemporary cognizance of V. Shantaram’s return to traditionality and idealism, and even though critics have applauded the film’s temporary flight to radical thinking – owing to the film’s social/political contexts of production –Nirmala’s submissive attitude allows audiences to concentrate upon the apathy experienced by Kaka Saheb. I reckon that viewer-sympathy equally gets punctuated by the fact that Kaka Saheb neither exercises his masculinity or social dominance nor exploits or abuses Nirmala, despite receiving immense pressure/support from his paternal aunt and the freedom that lawlessness[ii] permits. He just silently suffers, and his inactivity becomes heroic. Ultimately, the focus shifts from Nirmala – and the plight of uneven marriage – to Kaka: his broken mental state(s), his guilt and redemption, his disintegration of identity, and his sacrifice.

Back in 1937, it must have been impossible to view Kaka Saheb’s “sacrifice” – his suicide – as a liberatory phenomenon/occurrence; more because that was not the director’s intent. Duniya Na Mane impinges upon social psyche to overshadow Kaka Saheb’s suicide as a karmic event. It’s viewed as a byproduct of injustice and inhumanity; however, postmodern viewers must not fail to realise that Kaka Saheb’s suicide serves as a catalyst to Nirmala’s emancipation, and that is because it occurs after Kaka Saheb insists Nirmala to apply sindoor in his name as her father, and not as her husband. It was in Kaka Saheb’s acceptance of his initial blunder, and of Nirmala as his daughter, that he discovers the power to sacrifice himself for the girl whose life he almost ruined. He understood the indispensability of his death for Nirmala’s freedom, because he also must have realised that in the absence of any marital law, Nirmala would not be able to divorce him, and that it was only through his death that Nirmala could be set free. His suicide note was, therefore, key in understanding Kaka Saheb’s pretext. This climatic volta changes the trajectory of character-centrality within the narrative, and (re)modifies Duniya Na Mane as an avant-garde tale of mental breakdowns, guilt, disillusionment and loneliness – seen through Kaka’s eyes. It’s further interesting to mention here that – in light of this alternative reading – the recitation of “Psalm of Life”, if not completely lose its original feminist context, could unequivocally be another evocation of Kaka Saheb’s values of sacrifice and paternal compassion, wherein these particular extracts seem to be sung exclusively for the former:

Lives of great men all remind us

We can make our lives sublime,

And, departing, leave behind us

Footprints on the sands of time;

Footprints, that perhaps another,

Sailing o’er life’s solemn main,

. . .

Seeing, shall take heart again.

Timelessness is a complex attribute to possess, and only a few early Indian films possess that: films like Chetan Anand’s Neecha Nagar (1946), Guru Dutt’s Pyaasa (1957) or Om Prakash’s Gateway of India (1957) come to mind, and it’s predominantly because these narratives allow alternative re-readings, thus remaining contemporarily fresh. V. Shantaram’s Duniya Na Mane is just another instance of this extraordinary juxtaposition of social criticisms and timelessness. In unveiling a parallel retrospection of this classic, I attempt to vindicate the diverse meanings that modern critical philosophies of deconstruction and intentional fallacy supposedly proffer and accentuate the possibilities of coalescing timelines via reviewing them from a refreshened perspective. Contemporary realities transform with time, and popular culture is regularly tested against this framework; and so, a Chaudhvin ka Chand (1960) might not “make sense” to many, and a Duniya Na Mane might just invite sympathy for a man who was purportedly considered a villain in 1937 . . . and this is where films qualify in terms of timelessness and polysemy. We could realign these films within any social decade, and yet they would retain their original self and illuminate diverse other meanings. In Duniya Na Mane, Nirmala’s plight is never negated; only that Kaka Saheb’s troubled psyche is equally placed within the framework of inquiry. It’s a world of inclusivity, and – as critics – it’s our obligation to understand all sides of a story. So, what if Duniya Na Mane is a sad tale of a sadder man? Tomorrow, it can be someone else’s.

Notes

[i]India’s first talkie film, released in 1931 (dir. Ardeshir Irani)

[ii]A reference to the fact the Hindu Marriage Act ‘55 was yet not known during the time of the film’s production.

Bio:

Ashish Dwivedi is a PhD student at the University of Southampton, researching on the cinema of Guru Dutt. His academic research circles around early popular Hindustani cinema, utopia/animation studies, modern literary theory, Indian literary aesthetics and dramaturgy. He’s also a creative writer and editor of poetry and (creative) nonfiction, and his work has featured in several international literary magazines/journals including Poetry Pacific, Oddball Magazine, Cine India, and Bandit Fiction.

***

Like Cafe Dissensus on Facebook. Follow Cafe Dissensus on Twitter.

Cafe Dissensus Everyday is the blog of Cafe Dissensus magazine, born in New York City and currently based in India. All materials on the site are protected under Creative Commons License.

***

Read the latest issue of Cafe Dissensus Magazine, “(Re)storying Indian Handloom Saree Culture”, edited by Anindita Chatterjee, Durgapur Govt. College, West Bengal, India.