By Nishi Pulugurtha

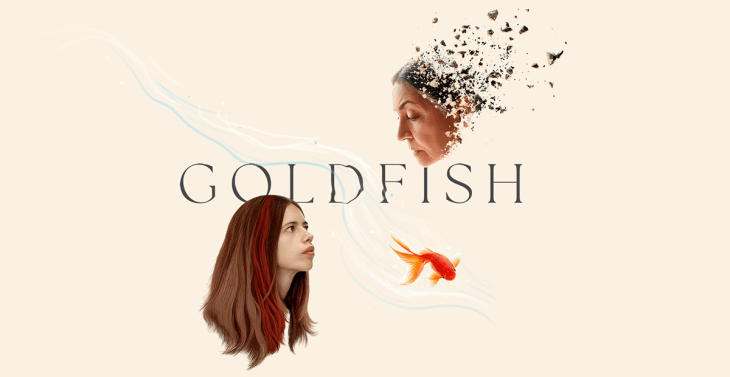

A daughter comes home as she finds out that there was a fire in her mother’s home, a fire caused by her mother’s forgetfulness. A neighbour calls her. This is the first time she has informed the daughter. Living in the diasporic space of London, the families on either side of the street hold on for each other. Laxmi gives Anamika a medicine with warning, that would calm her mother – it is to be used only when things get very difficult. She tells Anamika that her mother does not talk to her these days. Pushan Kripalani’s Goldfish running in a lone multiplex in Kolkata is a story of relationships, at whose centre is dementia.

The mother, Sadhana, has been diagnosed with dementia and refuses to get herself assessed for special needs. She knows she has dementia and is sure she can manage things. She wants to do things her way, the way she always did. She is happy to see her daughter, remembers her habit of having tea at four but forgets giving her the tea. Anamika is in a difficult situation. She is looking forward to a new job and when she is dropped home by her boyfriend she does not want him to go in and meet her mother. She is sure it would be plain awkward. Throughout the film they talk via video call. He telling her at times how difficult caregiving is, asking her to be practical.

When she goes out and tries to start her mother’s car, the neighbour gets suspicious. He is new to the area and is stopped by older neighbours who know Anamika, Sadhana Tripathi’s daughter. That she has come home after a really long time is a point that the film makes clear. The mother daughter relationship has been a strained one. As Anamika begins to stay and learn to manage things at her mother’s place, she begins to learn about her mother’s life a little at a time. The stories around music that had been and still is her mother’s passion. Music that she could not pursue seriously because of marriage and domesticity. The cassette player and the cassettes are seen and used frequently in the film. As they sit and talk in a scene, Sadhana speaks about two concerts that she attended, and how the smaller and less fashionable one turned out to be. As she talks about it, Sadhana speaks of her wish to be part of one such concert again, in India.

The use of the diasporic space wonderfully works to present a group of people, a community uprooted from their homes, working hard to create a new life abroad and sticking up for each one. It also represents the state of one who has dementia, one who is slowly going to become isolated and cocooned, who is slowly losing it all and knows that she is losing it. The sense of community becomes important once again as there is a talk of a virus and the masks that need to be used. The restrictions that the pandemic brings in, the mask that stifles, of being stuck at home, of the need to go out as things get difficult are referred to in the film. As Laxmi says, when she volunteers to spend time helping out with Sadhana, she needs to be out of her home for some time. The story of Laxmi’s life, the difficulties that she had to bear as she tried to find her way in a new land, away from home and family, is narrated by Sadhana. When Anamika, whom her mother calls Meeku, tells her mother that Laxmi will be coming over to be with her, Sadhana asks her if she was talking to Laxmi. With the degeneration caused by dementia becoming more pronounced, Sadhana finds it difficult to remember.

Anamika is surprised to see the several highlighter pens that her mother has. She even questions her mother about them. They are used to make notes, to help Sadhana remember things. She even makes audio recordings about things that she plans to do, so that even if she forgets, she can go back to listening to them. For someone who has been a caregiver for a loved one with Alzheimer’s disease, making small notes, putting them up on doors, and other places is an all too familiar scenario. As she packs her mother’s stuff, she opens her mother’s cupboard to find photographs with captions, Sadhana knows she will need them some time, to remind her of the people who matter in her life, including her daughter. Anamika stops for a while, removes the photographs, and puts them in an envelope, as her mother will need them in the care facility as well. She even packs some of the highlighter pens, the cassette player and cassettes; she seems to know things that mean a lot to Sadhana.

Anamika observes her mother moving through the house and settling things here and there. She comes into her room and just touches something on the cupboard to move away and go into the kitchen. There is an anxiety in her that is not overt, but it is clear that something is clearly troubling, something that she doesn’t understand. Anamika is not sure of how to handle it all. She gives her mother the medicine that Laxmi had asked her to use as her mother’s unsettled state disturbs her. She is there in several scenes as the observer, watching her mother closely. At times they sit in the backyard, smoking and looking at the fox that comes in at times. As they sit and talk, older disturbing memories haunt Anamika as she tries to come to terms with her mother – how her mother had made her to smoke a cigarette, how her mother had got her a goldfish when she wanted a dog for a pet and how her mother had flushed the goldfish and left the bowl. Sadhana tries to tell her that the fish was dead, something that Anamika does not accept. She accepts this much later when she empathizes with her mother’s state, as the roles of caregiving reverse. When she hears noises at night, she rushes out to check and on one such occasion she sees a hurt Sadhana in the bathroom. The neighbours have to be called to help her out.

Anamika comes to settle her mother in a care home; she visits one and towards the end decides on sending her mother there. Ashwin tells her not to keep Sadhana in her home, in her space as long it is possible to. This Ashwin she finds out is the man to whom her mother has willed her home. Her anger at her mother, at Ashwin, the stranger who seems to understand her mother’s likes and dislikes, is clear. Ashwin is a comforting presence to Sadhana. He knows how she likes her tea, of his gentle touch that seems to soothe her. She drapes herself in a beautiful saree as she comes down to have tea with Ashwin. The first time we see her in a saree is when she is out on the street, looking for a car to go to the BBC for a recording. It is clear then that Sadhana has muddled things. Anamika handles this situation with great care as she points out to her mother that the dates have been mixed up. Later Sadhana needs help and it is her daughter who helps her drape the saree as she gets ready to leave. The carers from the home arrive but then Anamika decides otherwise.

As Anamika finds out about her neighbours and the community in London, she gets help from the community. There is Tilly who stops in to help when Anamika needs to go out for a few hours; Ashwin and the others care about Sadhana. There is Angad who learns music from Sadhana something that Anamika had no clue of. As the several stories unravel, love and compassion become important ideas, particularly in a post-Pandemic world of restrictions.

Goldfish portrays the mother-daughter relationship beautifully as dementia becomes more and more prominent in the mother. There is a scene in the film where Laxmi has a stroke and falls, and Sadhana asks for some coke for her. This is the time when it seems that she knows just how to handle it despite what was happening to her. Cognition does not disappear all of a sudden and even when things begin to fade there are moments when there seems to be some clear thinking. When Laxmi’s ashes are taken away, Sadhana breaks into a song and fumbles for words. As she is prompted by Anamika, she goes on to sing. As they move on, the mother advancing in dementia and the daughter trying to decide on how to handle her mother’s situation, Anamika moves from some troubling memories, bad patches, conversations with her father (in voice overs) that happen throughout the film, to trying to make sense of her relationship with her mother. When these voiceovers happen, the screen is black, almost as if we are stuck in a dark world and don’t know what is happening – it almost seems to be the world of one who has dementia and the world of the Covid pandemic as well.

Goldfish beautifully depicts human relationships in its nuanced presentation of a character with dementia. It explores the difficult choices one needs to make, of love and holding on. With fabulous performances by Deepti Naval as Sadhana, revealing the nuances of one who has dementia and Kalki Koechlin wonderfully portraying the daughter troubled with her relationship with her mother, trying to manage her life and deal with the situation she finds herself in. Goldfish is a poignant story told with great care. There is no overt sentimentality and the subject of dementia is handled with great care and sensitivity. The film ends with the mother and daughter sitting at the table, by the window, having coffee, a break from their habits, a beginning of a new habit, of a new bond. She hands her the coffee mug and puts it into her hand making sure that her mother holds it well. She also makes sure she is keeps it on the table too. The reversal of the roles is complete.

Bio:

Nishi Pulugurtha is an academic, author, poet and occasional translator. Her publications include a collection of essays on travel, Out in the Open; an edited volume of essays on travel, Across and Beyond; three volumes of poems, The Real and the Unreal and Other Poems, Raindrops on the Periwinkle (Writers Workshop, Kolkata), Looking (Red River 2023); a co-edited volume of poems Voices and Vision: The First IPPL Anthology, a collection of short stories The Window Sill, an edited volume of critical essays, Literary Representations of Pandemics, Epidemics and Pestilence (Routledge, 2023). Her recent book is a volume of essays written during the pandemic, Lockdown Times. She is the Secretary of the Intercultural Poetry and Performance Library, Kolkata and is member, Advisory Board, Alzheimer’s and Related Disorders Society of India, Calcutta Chapter.

***

Like Cafe Dissensus on Facebook. Follow Cafe Dissensus on Twitter.

Cafe Dissensus Everyday is the blog of Cafe Dissensus magazine, born in New York City and currently based in India. All materials on the site are protected under Creative Commons License.

***

Read the latest issue of Cafe Dissensus Magazine, “(Re)storying Indian Handloom Saree Culture”, edited by Anindita Chatterjee, Durgapur Govt. College, West Bengal, India.