By Sonal

I first read Milan Kundera in the mid-2000s when I came across Immortality. This was a novel unlike any other that I had read. At the time I was pursuing post graduate studies in history. A mesmerizing blend of history and fiction, Immortality hit me in the face: what exactly is the relationship between past, memory and history? Rubens, in Immortality, discovered that memory does not make films, it makes photographs. In his remembrance of the several erotic encounters with women, he had only a few mental photographs, not a film of the motions in its tiniest detail. Rest all was perhaps recreated in his memory. This struck a chord in me as a historian in training. How do we reconstruct the past – personal or otherwise – if, with passage of time, the boundary between memory and imagination gets blurred? And what essentially recounting that past meant?

Trying to find answers, I found the Book of Laughter and Forgetting. It opened the doors to the questions of memory and history wide open. “The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting” not only placed all the epistemological violence in the history of humankind into perspective, but also the everyday power struggle of individuals in all their relationships at a very ordinary level. His brilliance lay in weaving historical episodes into the seemingly mundane lives of fictional characters underscoring that very struggle of memory against forgetting. That power, however, was not confined to that which was exercised by a totalitarian state against its political opponents alone. It might as well be the power that a lover exercised over his partner, or that what a mother had over her son. In this particular novel, Mirek wanted to erase the memory of his affair with a woman by getting back and destroying the letters he had written to her over years. While it may be possible for the state to erase the past, personal history may not be that easy to erase, for Jdena, his girlfriend, would not return the letters and by holding on to them, she had power over him. Jaromil, the protagonist of Life is Elsewhere, wanted to get rid of the power that his mother had over him, to the extent that she decided the underpants that he wore! The memory of the humiliation brought by the ugly underwears was far greater than any other memory he had which he wanted to get rid of and no matter what he did, each time he encountered the woman whom he couldn’t have because of his embarrassing underpants, he couldn’t forget his mother.

I remember the comic plot of Jaromil’s underpants in Life is Elsewhere distinctly. I had joined as faculty of History at an undergraduate college in Delhi teaching twentieth century world history, post second world war to be precise. The idea of using Kundera’s Jaromil, a celebrated poet in Communist Czechoslovakia, as an example came across my mind to explain why the Cold War was not confined to the dimension of geopolitics or weapons or political regimes alone. Milan Kundera became one of the most recommended authors, among others, by me to students to use literature to get glimpses of history. However, the comically tragic episode in the novel has been in my memory as one of the finest examples of the unintended consequences of state allocation of resources (as much as it keeps inflation under control) on everyday lives – something that we never really think about. Poet Jaromil’s era was that of war time austerity and elegant underwear was seen as a luxury. It was hilarious to read: “everywhere in Bohemia in that era men climbed into their women’s beds dressed like soccer players, going to their women as though they were entering the stadium.” It might appear frivolous compared to the larger narrative of the artists including poets having to conform to the party ideology under constant obligation that even their love poems should reflect that it was a work of a socialist poet. But our protagonist, Jaromil was a victim of both the state limiting his choices, and of his mother who gave him no choice at all, for she purchased his underpants. So, when he started seeing a woman, he hid a pair of better-looking gym shorts in his desk drawer and used them whenever he would go to his girlfriend. But one fine evening, after his poetry reading at an event for the state police, the event organizer, a beautiful woman invited him over to his place. What could have been an erotic moment in his life, he was too embarrassed to undress given his “bulky, ugly dirty grey underpants.” Kundera’s comic timing in describing all the possible ways in which he could have undressed so that the woman in question did not see his underwear, but his embarrassment making him leave instead, was an absolute joy to read. He was enraged at his underpants, at his lost opportunity but more than anything at his mother! But for the reader the plot is nothing but pure humour. Dark humour.

The overwhelming presence of his mother in Jaromil’s life could have infinite possible narratives. But a non-judgemental matter of fact narrative is what sets Kundera apart from writers of his age on the subject. When pregnant with Jaromil, her husband had been seeing a Jewish woman. He continued seeing her even after the German occupation of Bohemia when the Jews were ghettoized by the Nazis. He continued to visit her in the ghetto and ultimately nothing was heard of them. It is left to the readers to decide what was more tragic: a pregnant woman losing her husband to Nazi war crime; or she being cheated on and not having had a chance to confront him before he died; or that her cheating husband was considered a hero for not giving up on seeing his Jewish mistress in the ghetto; or her overwhelming presence in her son’s life to fill the void in her life or the milieu itself.

The personal and the political in his novels are so intricately intertwined that it would be an injustice to the literary genius to confine him to dissident ideas in a Communist regime. True that born and brought up in the times of war and revolution, Kundera’s works give us glimpses of those times. A multi-ethnic liberal democracy’s invasion by Nazi Germany, its subsequent liberation by the Soviet Union and the establishment of a Communist regime in the post-war make the backdrop in most of his novels. Stronger undercurrents are those of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, Prague Spring, persecution of the political opponents. As Czechoslovakia witnessed reforms and later split into ethnically distinct countries, Kundera’s writings also capture changing times. However, the nostalgia for Prague, the one possibly in his memory, continued to elude the author even when he became a French citizen and established himself as a French author. Milan Kundera’s novels and characters transcend thus the limited history of revolutionary Czechoslovakia. This is not to undermine the roots of the author or the historical settings of his plots, but only to suggest that there is a timeless ambiguity about his characters.

These characters are driven by the basic human emotions, elementary questions that bring the individual in conflict with the state and the fundamental conundrum of the distinction between the personal and the political, especially when it comes to the politics of the sexual body: questions that cut across the spectrum of ideological left or right. Two comrades in arms can come together in physical intimacy under the influence of an adrenaline rush emanating from the pursuit of the cause of a better future. This attraction may even obliterate momentarily the subtle or grave difference of opinion regarding the fate of the class enemies they had identified together. That adrenaline rush may even make the man overlook the fact the woman was ugly, something he was always aware of. In that moment, even the cause of a better future takes a back seat. But having been spent in the raging passion of the bodies, the cause for humanity once again occupies the centre stage; the ugliness becomes a source of shame and sexual act itself turns into ridiculous motions. As if this isn’t complex enough, the lovers begin to see each other as a political trap set up by the totalitarian state to out the opponents. While parting of ways might be plausible, the power of being known so intimately by one’s lover was a fear far greater than the state prying in personal lives.

Interestingly, Kundera does not demonize socialism or communism itself in its entirety. In The Unbearable Lightness of Being, he is vehement in saying that the Communist State was not founded by criminals. It was founded by enthusiasts who believed that they had founded the road to a better future, a utopia, a paradise. But they were so convinced that this was the only better future, they committed crimes in coercing others to arrive there. He asks a fundamental question: could they be acquitted of their crimes if they had no knowledge of the paradise mistaken? In some ways, Kundera is suggesting what many authors of futuristic dystopian world order had written: the pursuit of a utopia results in a dystopia of sorts which is authoritarian. Kundera’s ideas in his novel underline the importance of individual freedom vis a vis the overpowering state power and ideology. His writings warn us of the perils of a totalitarian regime intolerant of the freedom of expression of individuals in which the persecution of political enemies leads to liquidation of a people by taking away its history, destruction of books and culture and even inventing new history and culture. He minces no words in pointing out that not only do such people forget what it is and what it was, the world forgets those people even faster: “The only reason people want to be masters of the future is to change the past.”

The Art of the Novel echoes this same play of memory and remembrance when he observes that man has always harboured the desire to rewrite his own biography, to change the past, erase his tracks, both his and others. And it is this existential urge to erase the past that in due course acquires a political level. “Remembering is also a form of forgetting,” he elucidates in Testaments Betrayed. What an individual or a nation chooses to remember or chooses to let go into oblivion, emanates in that existential urge to rewrite one’s past. Each time I fathomed his philosophy of memory, of forgetting, of power and of history, his next novel threw a curveball. In Slowness, he adds the dimension of passage of time with respect to memory: the degree of slowness is directly proportional to the intensity of memory and the degree of speed to that of forgetting.

In the polyphony of his art, memory, thus, is the common thread running through each of his masterpieces. Nostalgia, the longing to return, is another manifestation of the interplay between memory and history. Unlike the memory associated with struggle between man and power, nostalgia is the longing for that what has been lost. The story of two Czech emigres in France, returning to Prague narrated in Ignorance tells us that the emigrants have different memories of their time spent in Prague as well as with each other. Their nostalgia was different from each other’s. However, there is an inherent contradiction in memory and nostalgia. Borrowing from Odysseus’ journey, the author notes that the people of Ithaca retained many recollections of him during his absence, but never felt nostalgia for him. On the other hand, Odysseus suffered nostalgia but remembered nothing. He underlines the necessity of evoking the recollections, of remembering the past again and again, if memory has to function well, “memories have to be watered like potted flowers, and watering calls for contact with the witness of the past.” That clicked the gear of memory, memorials and history in motion: the need for memorialization of past events of a nation to keep alive its collective nostalgia for a (re)-imagined pasts, the necessity of keeping the memory alive, like a potted plant.

Even though Milan Kundera’s body of work is definitely not History 101, the historian in me revelled in Kundera’s wisdom to delve deeper into the philosophy of memory and history. The unforgettable characters in his novels are individuals as they are, and not as they ought to be. In The Art of the Novel, Kundera warns us that in seeking the political information, we often lose the aesthetics of the art of the novel. However, his art, rich in philosophy, cynicism and humour, was never lost in the political expose of the times he wrote about. The surreal hedonism of the characters, their reflections on the politics of the body, can make this essay acquire the shape of a thesis. But it should suffice here to say that Kundera was not only a master storyteller, but a philosopher with an edge of cynicism. Over the years, while I am still studying the philosophy of History, understanding authoritarian regimes across the world in historical perspective, a thought often crosses my mind: Kundera’s characters and plots could have been situated in any country where an entire generation is swept away by an ideology which promised a better future for its people. In his case, it was the promise of a better future for the Czechs in times of German invasion and for a brief while socialism did fulfil the promise of a better future, until the revolutionary state turned totalitarian. After that, even committed party workers like Kundera himself were expelled from the party for questioning its authoritarian ways. I am sure readers across the globe who have witnessed ideological fanatics trying to prevent dissenting opinions could relate to his novels, characters and ideas regardless of the ideological underpinnings of Communist Prague or the western liberal democracy.

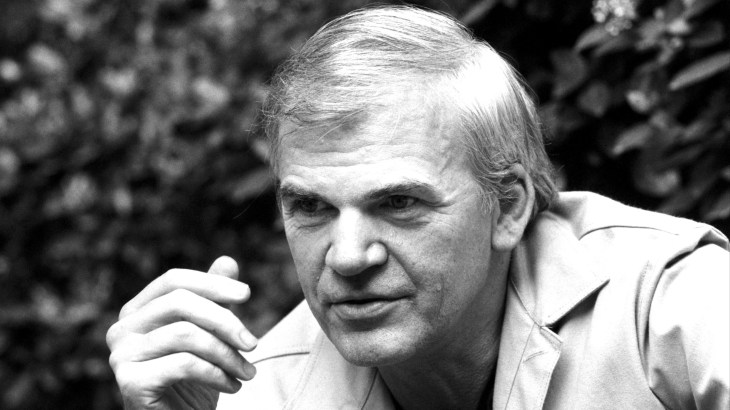

Milan Kundera’s passing away recently has resurfaced the memory of the times in which wrote: ethnic persecution, ideological rivalry, censorship and freedom of expression, state vs individual freedom, and his celebration in the western liberal world in the times of Cold war as a dissident Czech writer. Tributes to the literary wizard have been pouring in from all quarters. It’s been overwhelming for English language readers like me who waited patiently for each English translation that arrived in the market, to know that there will be no more waiting for another piece of his work and the joy of finding one. What exists is only a nostalgia for the hope of meeting the author in his characters the way the author met his character, Agnes in Immortality viz., in small gestures. But to borrow from Kundera, nostalgia is a confirmation of the past that is lost, it can never be relived, only reconstructed from the photographs in the memory.

Bio:

Dr. Sonal is historian based in Delhi. She specializes in the colonial period in South Asian History. She has been a Chares Wallace India Trust Fellow and a Visiting Fellow to the Yale Center for British Art, Yale University.

***

Like Cafe Dissensus on Facebook. Follow Cafe Dissensus on Twitter.

Cafe Dissensus Everyday is the blog of Cafe Dissensus magazine, born in New York City and currently based in India. All materials on the site are protected under Creative Commons License.

***

Read the latest issue of Cafe Dissensus Magazine, “(Re)storying Indian Handloom Saree Culture”, edited by Anindita Chatterjee, Durgapur Govt. College, West Bengal, India.