By Shonima N

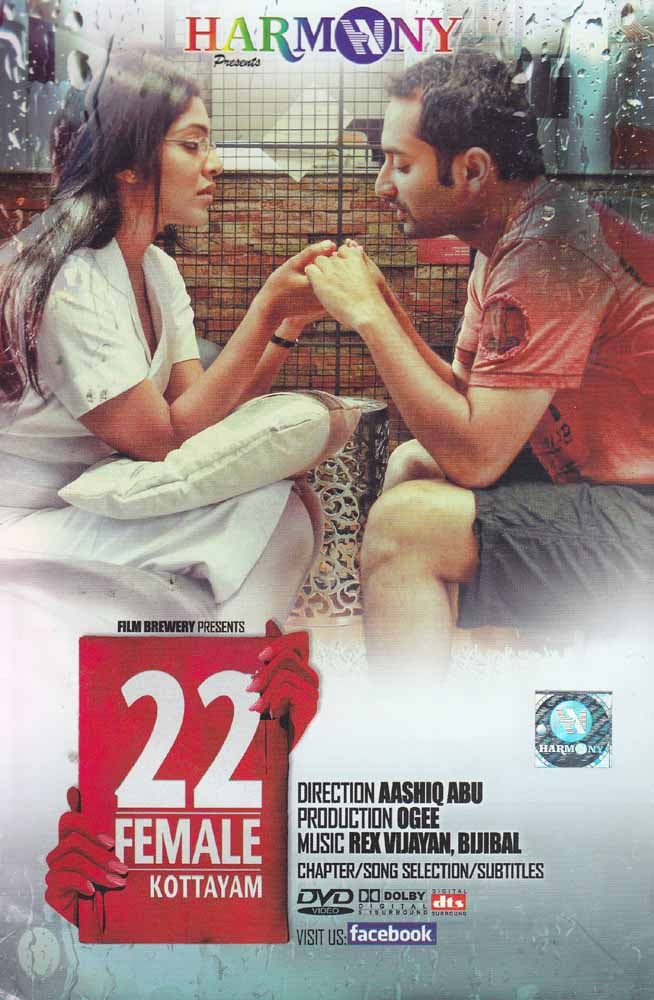

When Tessa in 22 Female Kottayam objectifies her own body to exploit men’s sexual interest to take revenge on them, we as viewers feel less empowered and more disgusted on seeing this female representation. This makes the audience take a step back and wonder if the new generation cinema really presented us with empowering and bold women representations as it had claimed. What we see in films like Salt N’ Pepper (2011), Chaapa Kurishu (2011), and Trivandrum Lodge (2012) set in urban spaces is the emergence of middle-class female protagonists that openly flirted, drank in public and delivered lewd dialogues all in the name of empowerment. Is this true empowerment or a post-feminist deliberation where the cinematic representations again cater to male libidinal desires in the guise of female individuality and freedom? To understand this, we must focus on the spatial dynamics that are at play in these films and how they are different from the new Malayalam films set in small-town spaces.

In all these new-generation films what is common is the urban space of the city that becomes the backdrop for the narrative. In Salt N’ Pepper, Maya is portrayed as an independent woman working as a dubbing artist in Trivandrum and her financial freedom is emphasised by her consumption of alcohol. Chaappa Kurishu reimagines the stereotypical binary of pure angel and immoral vamp through the new narrative of female sexuality opened up by the city spaces and globalising commodity culture. Here, the sexually open character is not portrayed as being villainous but is instead portrayed as vulnerable for being both a desiring and a consuming subject. In Trivandrum Lodge, the female protagonist Dhwani decides to stay in the masculine space of a lodge considered unsafe for women from ‘good’ families. Here, Dhwani becomes the flaneur out for new experiences in the city especially voyeuristic gazes from males, inappropriate touching and sexual innuendos. In these films what goes unnoticed is that female individuality and boldness are equated with sexual submission and explicit dialogues. Although these films explore the performative spaces of women’s desires through images of sexualised middle-class female consumer figures, the women being represented as independent refuse to question patriarchy’s hidden desires and thus end up becoming the victims of the same. By objectifying female sexuality these films offer us images of a new globalised woman disconnected from the dynamics of family. What these films then offer is the notion of family as a sacred space wherein gender relations should neither be violated nor questioned. In essence, by focusing on the individual far away from the institution of family these films cater to male fantasies and perspectives in the urban space of the city and thus do not challenge existing notions of female status and familial norms. Despite the radical and unconventional portrayals of these female characters, they avoid facing patriarchy and its established morality head-on.

The city as a space thrives on anonymity. It is one of the marked features of urban spaces where no one truly knows the other. Community formation is relatively hard in urban spaces because of globalisation and people moving around rapidly from one place to the next. This lack of community formation on the one hand provides freedom from the traditional shackles that usually weigh the women down but at the same time, this also means that new forms of gendered violence can creep up in these anonymous spaces. The city space is also considered a masculine space because of its openness where anything is possible. In such a space deemed masculine, for a woman to assert herself she has to showcase her sexuality and even objectify it. It is only by doing so that she feels in control of her space and even then, she is subject to the male desires and does not possess any control whatsoever. The new generation cinema and their celebrated female protagonists become empowering representations only superficially.

This superficiality primarily arises because these urban representations of women do not tackle patriarchy in their everyday spaces and instead use the explicit display of their sexuality to seem empowered which they are able to do as they are in a space away from the family unit. This superficiality of new-generation films comes to light when we take a look at some of the new Malayalam cinema set in small-town spaces. These films being set in small towns or villages place themselves within the imaginary of family and community as a social unit. Such a shift from the urban city space to small towns provides a space for questioning and redefining representations of gender and sexuality. The female characters in films like Kumbalangi Nights, Helen, Ishq, and Kismath neither objectify their own body to the point of being overtly sexual and lewd just to cater to male fantasies nor are they submissive to patriarchal demands. What comes into focus in these films is that despite being fixed within the stable dynamics of normative heterosexual family units, the female protagonists in the films voice themselves and stand their ground. Here the characters no longer escape from the family space and move to a city space detached from their familial ties to establish themselves. They do that within the community space that a small town as a setting offers. This naturally foregrounds questions surrounding work culture and worker’s familial culture as seen in films like Kumbalangi Nights and Helen.

In Kumbalangi Nights, Baby Mol works as a tourist guide and her family runs a homestay while the titular character in Helen works part-time at a restaurant called The Chicken Hub. Both of them are placed close to their family space. While Baby Mol lives and works in the same village of Kumbalangi known for its integrated tourism project, Helen works in a posh mall in the city of Kochi where even though she is placed in city space, at the end of the day, she has to come back from work to their family space in a small town. This proximity has affected the work-life balance which is the equilibrium between personal life and career work. This equilibrium in the earlier times was made on gendered terms where men were the only ones who concerned themselves with work while women remained in the domestic sphere taking care of the family. With the entry of women into the workplace, the gendered maintenance of the equilibrium skewed and the radical separation between work culture (career) and worker’s culture (family) began to blur. This contestation that arises from the blurring is represented in the films by the introduction of the brother-in-law Shammi and the police as characters respectively.

In Kumbalangi Nights, Shammi takes up the role of the father figure and slowly becomes the patriarch of the family. Shammi interferes with Baby Mol’s job when he tries to morally police a foreign guest staying at their homestay. This situation adversely affects Baby Mol’s work and she reminds him how the rating and review of these guests matter to her work. In reply to this Shammi recounts the real-life incidents that happened in other homestays in hopes of showing her how she is ‘at risk’. In the case of Helen, it is not exactly Helen’s family that stands against her but the police. When Helen is caught with her Muslim boyfriend Azhar late at night for driving irresponsibly, the police create unnecessary complications on religious grounds by moral policing and calling her father into the station so that they can see how “loose” their daughter is. The police officer also tells her father that they are aware that they need not morally advise these youngsters as they do for college students as they are working individuals. The irony of the statement resounds clearly when they do exactly that with no regard for the individual’s personal life or work culture. Such oppositional behaviour points to the neoliberal paradox which expects its subject to be moral whilst being capitalist and such a bridging of neoliberalism and neoconservatism involves serious implications for women as it drastically affects their spatial experience where neoliberalism empowers women at the same time that it controls them.

The 2016 film Kismath tells the real-life story of two young lovers: a 28-year-old Scheduled Caste (SC) girl and a 23-year-old Muslim boy from a place called Ponnani, north of Kerala. The cinematic depiction of the frustrations and anxieties of Anitha and Irfan brings into focus how the police function as a network within the community that reinforces traditional moral and casteist values. Policing works best when it can network people within the communities as informants and spies to supervise individuals without being seen. This is especially true in the case of small towns. The effectiveness of small towns and rural policing is highly dependent on the regular and often personal interactions between police officers and individual citizens. Unlike cities, this sort of networking in rural and small towns makes the police a part of the community. The police become a network system in the community which is used by society to protect their cause. Just as Irfan’s brother and father seek the help of the police to scare the couple so that they will separate in fear, the network system of police in small towns and villages is always taken advantage of by the upper sections of society for their gain. The police also need their help and thus yield to their needs and it then becomes a network of interdependent power dynamics. Here, the police become not just a localised vertical power that is part of the modern nation-state but also acts as a horizontal power of pervasive surveillance that is diffused across the social body.

While in Kismath we see how the police become the guardians of morality, in Ishq, we see how the mere impersonation of being police allows the local people to exercise authority and become moral policers. The effectiveness of policing to regulate and control individuals rest on its panoptic dimension where the idea of omnipresent continuous surveillance automatically transforms the subjects (individuals) into an agent that self-polices itself. The more the policing gaze becomes invisible and unnoticeable, the more the gaze moves away from being a panopticon to a social relation. In the film when Sachi and his girlfriend Vasuda are being affectionate in their car, the moral policers round-up on them taking their video and asking “Enthanu paripadi?” (What are you two up to?) Although Sachi tries to dissuade them initially, upon thinking that they are policemen, he becomes interpellated as a subject and submits to the Subject by immediately addressing them as ‘sir’. The subject internalises moral policing and regulates one’s behaviour oneself without the intervention of an external other as he tries to justify himself. The ‘inner cop’ in every subject appropriates himself/herself within the cultural context of moral policing through the discourse of risk. The subject accepts one’s submission and regulates oneself even in the absence of police violence because there is always the presence of risk in the form of a threat of violence. This perceived risk that permeates the individual’s life is what forces one to actively police oneself and submit to the Subject.

Ishq also lays bare how masculinity is shaped and structured by other masculinities and by patriarchy that runs as a network in society. The police become the symbol of ideal masculinity of authority, control, violence and morality. The police being the state authority hold the power to which all others have to submit ideologically or through violence and this lets them take charge of any situation, control the end result and maintain social order. The two men, on taking up the guise of being police officers, are able to inflict mental agony on the young couple by making them justify themselves, their relationship and their personal life. By invading the privacy of the couple, it is the men who are going against the rights of individuals but the mantle of being ‘the police’ automatically gives them power and control over the couple. It is through the helplessness of the couple that they derive pleasure and their masculine power. By indulging in moral policing publicly they are satiating their lust privately by playing the power game of domination-submission. Later on, Sachi also becomes a part of the patriarchy when he defines his masculinity in terms of Vasuda’s chastity. While Vasudha tries to move on from the incident, it is Sachi who goes after the perpetrators and tries to take revenge on them because his masculinity depends on it. There is a scene in the film where after taking revenge and knowing that Vasudha is still chaste, Sachi smilingly leans in front of his car and replays the scenes. Here the replaying does not happen in some flashback but plays out in the very car he leans on as the camera moves closer to it. This shows how much Sachi is obsessed with the event. This obsession with revenge ultimately leads Vasudha to end the relationship as she realises Sachi is just another man caught in the network of patriarchy defining himself through it.

Whether it be the growing tussle between work culture and worker’s culture as seen with the films like Kumbalangi Nights and Helen or the community network that perpetuates gendered discrimination as seen in Kismath and Ishq, the new Malayalam cinema set in small-town spaces explores how the structural inequalities within the society affect women. Unlike the new generation cinema which, being set in urban spaces, can only articulate the dimension of gendered violence from the perspective of the individual, the newer localised films can highlight the roles family, police and community play in the same. By portraying women as entering the public space of work within the family space of small towns and villages which is otherwise considered as the private domestic space, the new Malayalam cinema has even begun to blur the dichotomy of private and public assigned to small towns and city spaces respectively. Thus, changing cinematic spaces not only brings changes to the representations of women but also brings forth changes in the perception of the spaces themselves. By centring the narrative in and around the community, these films bring into light the gendered dynamics reinforced and reiterated in society with its existing social patterns. This emphasis on structural inequalities enables one to look at gendered violence inflicted on women from a new perspective where the individual victim is no longer at blame. Such a view is much needed for society at this time when neoliberalism and globalisation open up career opportunities for women within their own community spaces. By focusing on small towns, the new Malayalam cinema has brought to life empowering female representations who are able to voice their resistance from the very place they stand to break free from the structures that was suffocating them since time immemorial.

Bio:

Shonima N. is a PhD researcher working on Malayalam cinema at the Department of Cultural Studies in the English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad.

***

Like Cafe Dissensus on Facebook. Follow Cafe Dissensus on Twitter.

Cafe Dissensus Everyday is the blog of Cafe Dissensus magazine, born in New York City and currently based in India. All materials on the site are protected under Creative Commons License.

***

Read the latest issue of Cafe Dissensus Magazine, “(Re)storying Indian Handloom Saree Culture”, edited by Anindita Chatterjee, Durgapur Govt. College, West Bengal, India.